Artificial Intelligence (II)

Please become a paid subscriber.

Continued from Artificial Intelligence (I)

One thing we should all have learned over the last half-century is to be particularly wary of Valley crusaders of any stripe. Like all Valley heroes, Mr. Altman made buckets of money, then turned to help mankind. Most Valley heroes, except the exceptionally honest, claim they were helping mankind making their buckets of money. From the beginning, the Valley has been ruled by self-interested profiteering, despite their incessant PR and virtuous phrasing about humanity's future. Certainly in America there has long been no shame in self-interested profiteering, but it ain't great politics, even if we’ve been incessantly assured this determinative ethos of established capitalism is all for the greater good.

In a most anti-capitalist and un-Valley-like statement, Altman claimed he had “more money than I could ever need,” and altruistically found the nonprofit OpenAI in 2015. At the time, Altman believed artificial intelligence was moving fast, arguing, “It’s uniquely dangerous to have profits be the main driver of developing powerful AI models.” The WSJ article continues, “Backers say his brand of social-minded capitalism makes him the ideal person to lead OpenAI.” All very noble, right?

In the words of the bard, there's the rub, the computing power necessary to implement an AI program is well beyond the financial means of any nonprofit. So, Mr. Altman makes a Faustian bargain with Mephistopheles himself, “The company signed a $10 billion deal with Microsoft in January that would allow the tech behemoth to own 49% of the company's for-profit entity.” Say whatever else you will about Microsoft, they are proudly institutional self-interested profiteers.

Mr. Altman apologizes in a recent post, in the footnotes amusingly enough,

“When we first started OpenAI, we didn’t expect scaling to be as important as it has turned out to be. When we realized it was going to be critical, we also realized our original structure wasn’t going to work―we simply wouldn’t be able to raise enough money to accomplish our mission as a nonprofit.”

Adding,

“We now believe we were wrong in our original thinking about openness, and have pivoted from thinking we should release everything (though we open source some things, and expect to open source more exciting things in the future!) to thinking that we should figure out how to safely share access to and benefits of the systems.”

Phew, honestly you can't parody this. In the blink of an eye, or better in the opening and closing of a transistor gate, out goes concern about profits as a dangerous main driver and then a partnering with the most virulent corporate champion of intellectual property, so much for any idea of openness. Whatever popular claims to the benefits of self-interested profiteering, there are absolutely none to the pursuit of unfettered power, just ask Doctor Faustus.

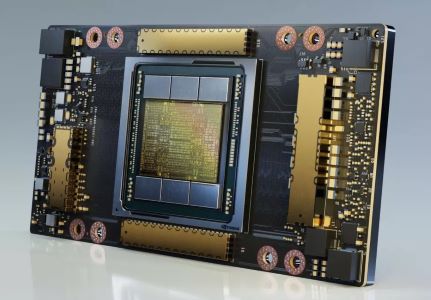

The necessary hardware for what's dubbed AI is truly incredible. The central process unit (CPU) of your PC replaced by layers upon layers of GPUs (graphics processing unit), which can better be specifically designed/programmed. GPU development was largely pushed by the computer game industry and their need for greater power. The particular A100 chip for OpenAI and Microsoft's partnership is manufactured by NVIDIA. This graphics card has 54 billion transistors! It is estimated the MS/OpenAI system requires 30,000. So 30,000 X 54,000,000,000, that's a number well beyond the comprehension of our natural intelligence. Whatever else AI is, it is brute force compute.

The GPUs are networked together in layers. Using programming models, the data gets pushed across these layers, back and forth, in a nonlinear process, meaning any given processor needn't wait in-line to process the batch of data it's assigned. Each pass through the layers results in more accurate data. In this way, system is “trained” by models to more and more accurately recognize presented data. The process is called deep learning. (This is a very simplistic general explanation of what is an elaborate technological process requiring ever more complex math).

Every piece of data is eventually converted into a number, a binary switch of either 1 or O, the programming reliant on ever more complex mathematics and ever more sophisticated applications of our knowledge of quantum physics. The transistor, the core of present computer processing, is a product of the same science as the atomic bomb. We are slowly discovering this compute technology derived from the same science of quantum physics, a science itself only a century old, is in many ways no less powerful and potentially destructive as nuclear weaponry.

Like all learning, AI is reliant on repetition. OpenAI writes, “Training a neural network is an iterative process.” So it would seem just like it's human creators, AI digs repetition. Yet, NVIDIA warns,

“However, since the wild successes of deep learning after 2012, the media often picked up on the term neuron and sought to explain deep learning as mimicry of the human brain, which is very misleading and potentially dangerous for the perception of the field of deep learning. Now the term neuron is discouraged and the more descriptive term unit should be used instead.”

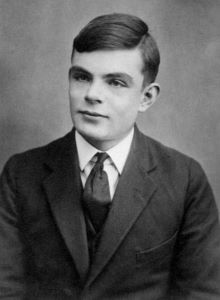

So, is this intelligence or not? I use to think Alan Turing's, one of information technology's initial developers, test for whether something was actual artificial intelligence was somewhat specious. It basically concerned asking a machine questions and if you couldn't tell it was a machine by its answers, that was a artificial intelligence. I've come around to think it might very well be the best definition. Machine intelligence is not the same hardware, wiring, and programming as animal intelligence, but if the results are similar or the same, it doesn't really matter. In fact, a machine's ability to store mass amounts of data and have it instantly available is already far superior to any animal's capabilities, including Homo sapiens.

Arguing whether or not this is intelligence is not greatly useful. Even worse is to dismiss the initial technology pointing at bugs or its present limitations, make no mistake it will get better. The bigger questions are what is the current technology's capabilities and how or even if any given capability should be implemented. In answering these questions it’s important to look at the impact information technology's already delivered in its very brief history.

Mr. Altman's warning against profits being the main driver for implementing this new generation technology was based on an understanding of the industry's short history. Mr. Altman's partnering with Microsoft insures profit will be the exclusive determining value, including determining the actions of Google, Amazon, and the handful of other corporate leviathans racing to implement.

This technology will quickly and decisively impact two areas of the economy. First, it will be an even more massive job destroyer, though not limited to the destruction of blue collar manufacturing, low level paper shufflers such as secretaries and travel agents, or service providers like cashiers. AI's job destruction will include many white collar professions, as Chairman Gates greedily rubbing his hands together lists “tasks done by a person in sales (digital or phone), service, or document handling (like payables, accounting, or insurance claim disputes).”

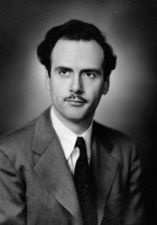

The great historian of technology Marshall McLuhan documented the job as an invention of industrialism. Before the Industrial Age, you were simply a farmer, it wasn't a job, it was who you were. Or the Nazarene carpenter, carpentry wasn't his job, it was who he was. Established industrial economics and industrial values will not provide useful measures of worth for this technology. It's certainly imperative when considering how or if to utilize this technology, we understand it will upend many established social conventions, requiring a need to transcend them.

Secondly, unimpeded, AI will facilitate an even more massive concentration of wealth. Popularly, wealth concentration is too often represented by personalities such as Gates, Bezos, and Zuckerberg, but it is much more useful to understand economic concentration in terms of colossal corporate power. As Fortune points out, presently two-thirds of the US economy is represented by the Fortune 500, who employ 10% or so of the workforce, which means 90% of the rest of us are chasing the remaining third. Also, it is far too little understood how the previous growth of IT and its installed infrastructure has been most extensively utilized by internal corporate systems, allowing in no small measure the last half-century's rise of corporate globalization.