Binding Prometheus

“Nearly every age and stage of culture has at some time or other sought with profound irritation to free itself from the Greeks, because in their presence everything one has achieved oneself, though apparently quite original and sincerely admired, suddenly seemed to lose life and color and shriveled into a poor copy, even a caricature. And so time after time cordial anger erupts against this presumptuous little people that made bold for all time to designate everything not native as "barbaric.'" - F. Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy (1872)

In the last half-century, American culture, if on cue, turned against the Greeks, a revolt succeeding in unmooring culture, casting it adrift, indeterminate in direction. The great irony, and all revolutions have their irony, the Greeks were largely responsible for the logic underlying scientific thought and its technological progeny. With the untethering from Classical Culture certain wisdom was lost. Most importantly, the lesson all knowledge gained and implemented is accompanied by certain troublesome consequences, call it tragedy.

In the poet Aeschylus' play, Prometheus Bound, this understanding lies at the heart of the hero's torment and trials. Prometheus is a Titan. In Greek lore, the Titans ruled the universe before the gods of Olympus – Zeus, Athena, Apollo etc. – overthrew them. Against Zeus' wishes, a dethroned Prometheus looked sympathetically on emerging humanity, bestowing upon us knowledge, science, and technology.

Prometheus gifts are best represented by fire, but he lists others,

“Yes, and numbers, too, king of sciences, I invented for them, and the combining of letters, creative mother of the Muses' arts, with which to hold all things in memory... to the chariot I harnessed horses and made them obedient to the rein, to be an image of wealth and luxury. ”

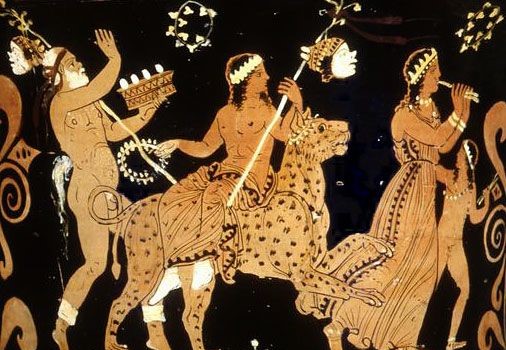

Prometheus' actions outraged Zeus, who bound Prometheus upon a high ledge and caused an eagle to continually consume his perpetually regenerating liver. Aeschylus' play was performed for the whole city of Athens during the great annual festival to the god Dionysus, whose worship produced Greek tragedy.

In The Birth of Tragedy, Friedrich Nietzsche says Prometheus' story is a sibling to “the fall” in Genesis, where Adam and Eve upon eating the forbidden fruit from the tree of knowledge are cast from Eden, the cunning serpent is condemned to crawl on its belly and east dust. Nietzsche sums it up,

“The presupposition of the Prometheus myth is primitive man's belief in the supreme value of fire as the true palladium of every rising civilization. But for man to dispose of fire freely, and not receive it as a gift from heaven in the kindling thunderbolt and the warming sunlight, seemed a crime to thoughtful primitive man, a despoiling of divine nature. Thus this original philosophical problem poses at once an insoluble conflict between men and the gods, which lies like a huge boulder at the gateway to every culture. Man's highest good must be bought with a crime and paid for by the flood of grief and suffering which the offended divinities visit upon the human race in its noble ambition.”

Knowledge lies at the foundation of tragedy. In early Greek culture, exemplified by Aeschylus, this tragedy is celebrated. Nietzsche points out tragedy is best expressed in the dichotomy of the two Greek gods, Apollo, representing the self-aware controlled individual, and Dionysus, who represents the chaos of the greater natural world.

He explains of Apollo,

“As a moral deity Apollo demands self-control from his people and, in order to observe such self-control, a knowledge of self. And so we find that the aesthetic necessity of beauty is accompanied by the imperatives, "Know thyself," and "Nothing too much."

In opposition is the god Dionysus, representing not the sculpted Apollonian individual, but the uncontrollable, indeterminate, endlessly changing, collective whole of nature. The Greeks understood despite our ordering knowledge, we always remained part of disordered nature. Nietzsche writes,

“In Dionysian art and its tragic symbolism the same nature cries to us with its true, disassembled voice: 'Be as I am! Amid the ceaseless flux of phenomena I am the eternally creative primordial mother, eternally impelling to existence, eternally finding satisfaction in this change of phenomena!'"

The festival of Dionysus celebrated the loss of Apollonian individual identity in a celebratory orgy of the whole, a reminder civilization remained subservient to the greater forces of nature. Nietzsche beautifully describes the eternal interplay of the individual and this greater absolute,

“The Dionysian and Apollonian elements, in a continuous chain of creations, each enhancing the other, dominated the Hellenic mind; how from the Iron Age, with its battles of Titans and its austere popular philosophy, there developed under the aegis of Apollo the Homeric world of beauty; how this "naïve" splendor was then absorbed once more by the Dionysian torrent, and how, face to face with this new power, the Apollonian code rigidified into the majesty of Doric art and contemplation.”

Nietzsche lamented this high point of Greek culture, the embracing of tragedy, lasted only briefly, destroyed by, in what I always found most amusing, Socrates and his logical methods. Birthed from Apollo, this logic developed an idea of control not simply of the self, but of the greater natural world, eventually leading to modern humanity's misbelief we can transcend nature. Nietzsche writes of our times,

“Our whole modern world... proposes as its ideal the theoretical man equipped with the greatest forces of knowledge, and laboring in the service of science, whose archetype and progenitor is Socrates.”

Modernity's great crime is the loss of tragedy, he criticizes, “Now we must not hide from ourselves what is concealed in the womb of this Socratic culture: optimism, with its delusion of limitless power.” What better describes the culture of technology in the 21st century? Nietzsche was always the 19th century's greatest critic of the 20th century and now the 21st.

This Socratic faith was wrought by a lost appreciation of nature by the compartmentalization, not simply of the human-self, but the categorization of the whole of nature. With science and technology, the Dionysian appreciation of nature's fluidity was subsumed in the misconceived belief Homo sapiens can control all that surrounds us. We removed ourselves from nature by dividing and shaping. We now worship technology.

This technological separation from nature and misconstrued dominance, created massive problems in regards to the destruction of nature’s womb and her teat which still nourishes. Today, the Socratic ethos of conquering and vanquishing nature seductively promises, as the snake once beguiled Eve, perpetrated technological offenses can be absolved with more technology, a mystical belief as fantastical as any ancient precedent.

Aeschylus provides a thought on how we might loosen the binds of Socratic culture. Prometheus laments his torment saying,

“Only when I have been bent by pangs and tortures infinite am I to escape my bondage. Skill is weaker by far than Necessity.”

Industrialism destroyed all understanding of the underlying power of necessity, praising and rewarding the skill of the technologist, ignoring the necessity of their creations. Necessity, not skill, moves nature. In an era where energy becomes more dear, water less bountiful, and food supplies grow erratic, the inimitable power of necessity resurfaces.

Aeschylus writes,

CHORUS

”Who then is the helmsman of Necessity?”

PROMETHEUS

”The three-shaped Fates and mindful Furies.”

Here the pre-Socratic Dionysian universe asserts itself. No matter our skill, we can never be separated from the forces of nature – the fates and furies – and resulting necessities. A century and half ago, the power of necessity was reintroduced to burgeoning modernity with the concept of Natural Selection. Into modernity, Dionysus reemerged, though has yet to in anyway reshape our industrial Apollonian identities. Once more, the world was made complex beyond human design. Life's history is of perpetual fluidity and ceaseless motion, all change effected met by another in return.

As that great Neo-Dionysian, Charles Darwin concluded, “There is grandeur in this view of life,” but to experience and benefit, as both Nietzsche and the Greeks understood, its underlying tragedy must be embraced. The understanding humanity will never separate ourselves from nature requires a rebirth of tragedy. A transcending of industrial culture is possible with a focus on necessity, a renaissance of ancient wisdom.