Citizen II

Today, citizen identity is nebulous at best, even though questions of “identity” define a great deal of American politics, such that it can be called politics. Popular or unpopular as the case may be, identity issues overwhelmingly concern matters of social and cultural definitions, horrendously loose sand to build any politics of substance. As Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka states, “Culture is a powerful weapon, but at the same time, culture can prove very, very feeble in the face of some really intractable situations.”

Much of the present discussion on identity should be left in university literature departments, incoherent graduate theses, and other intellectual bogs of deconstructionism, where word parsing is mistaken for insight. Nonetheless, this is not meant to deny in the 21st century, identity for the species homo sapiens is very much a fundamental issue. Identifying first and foremost as equal citizens would help construct a politics to meet the intractable challenges we face.

For thousands of years, we accepted technological evolution as a process beyond politics, despite such changes eventually completely defining us. In this century, two centuries of industrialization, which utterly reorganized the economy, culture, politics, and most intractably the environment, meets an entirely new revolution of information and biological technologies.

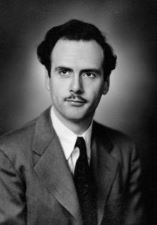

Six decades ago, a group of thinkers including Lewis Mumford, Kenneth Boulding, Jane Jacobs, Buckminster Fuller, and others attempted to get people to understand the importance of looking at technology as the foundation of human development. Their thought flamed briefly to attention and than just as quickly subsided. One of these interesting minds was the Canadian literature professor Marshall McLuhan. He wrote an excellent book called, The Gutenberg Galaxy, chronicling the five century impact of text and the book on society. He also provoked much thought with his book, “Understanding Media,” on the impact of the developing electric media, such as radio and television, and of the then nascent computer and information technologies.

McLuhan had some wonderful insights on how we needed to think about these technologies. He saw them as more participatory and encompassing media than the book. McLuhan states, “In this world of profound involvement, identity seems to vanish.” The resulting search for identity becomes an increasing preoccupation for all impacted by the technology. Across history, the search for identity has often been explosive.

He correctly foresaw the computer wiping out the job, the job being an industrial construct. Before industrialism, people were farmers, blacksmiths, masons, etc., these weren't jobs, they were defining purposes. In an information soaked society conducted across electric media, instead of jobs, people assume “roles.”

The great information tsunami created by these technologies breaks upon the world at the speed of light, completely reshaping the values, processes, and institutions of industrial society. McLuhan adds, “For the first time in history, there is more information outside of schools, than inside,” yet, “We encounter this new technology by translating it back into the old one.” This might be McLuhan's most profound insight – established precepts dominate our initial interactions with all new technology.

It is not that we don't understand technological evolution and its impacts, we don't even try. We are led not by what we want from the technologies, but simply by what the technologies can do. A politics of technology would confront this lack of thought and design, redefining the role of citizen. A redefinition starting with the simple fact that whatever our cultural differences, we are all homo sapiens sharing a small planet, all technological development impacts each of us.

Presently, the majority of established political power resides in two bodies, the federal government and massive corporations. The federal government is an Agrarian Era construct, while the corporation is an Industrial Age manufacture. Their precepts are of a different era, many increasingly detrimental. The structural anachronisms alone are analogous to having asked the agrarian feudal lords of old to lead the new processes of industrialization.

Reviving the citizen through redefinition requires a reorganization of our institutions, along with a freeing of information's shackles, whether institutional, legal, or systemic. First and foremost, how we as a society process information must be deliberated. This might best be facilitated by a multitude of participatory, distributed, networked associations, where information is created, edited, communicated, and decisions are made. These “cells” can be both locally based, where people physically meet, and electronically networked. Such models and methods can be used to reorganize both government and the corporation.

The industrial values of production and consumption with their established identities and values such as employee and quantity, need to be subsumed into the role of citizen and the processes of design. It is far too little understood the ultimate end of technological development is not the technology itself, but the greater environment every technology creates. Environments are not products, but systems that are fluid and circular, requiring constant input and feedback. Environments define their component parts, just as the parts help define the environment.

The role of citizen is the fundamental equal element upon which society can be reformed. In their role as citizen, people design their environments and thus define their identities. In a wonderful talk more than a half-century ago, Robert Oppenheimer, physicist and former Director of Los Alamos Laboratory stated,

“We live in a time which has few historical parallels. There are practical problems, problems of the restructuring of human institutions, of their obsolescence and inadequacy. And problems of the mind and spirit, which if not more difficult than ever before are different, and are indeed plenty difficult.”

In over fifty years since Oppenheimer's talk, we have not moved an inch.