Civilization -- All Roads Lead to Rome

Wandering the streets of Manhattan a couple thoughts had me wondering about civilization. Defining civilization is always difficult. For me, the key idea is civil, which Webster defines as “adequate in courtesy and politeness.” The essential word being adequate. Scratching the thin veneer of any historically recognized civilization, courtesy and politeness quickly fade. Such questions become painfully acute stepping into the Frick Museum on 70th street.

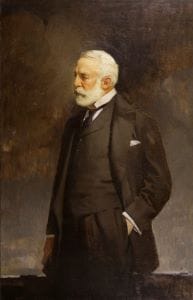

A collection of 15th to 19th century art is housed in one of America's Gilded Age baron's estates. These American industrial estates rose on the new continent in place of the old European feudal manors our best republican ancestors found so repulsive. On appearance, nothing screams civilized more than Mr. Frick’s wonderful art collection – Van Dyke, Goya, Whistler, Velázquez, David, El Greco, and any number of other beautiful paintings.

Frick was one of the tech-boys from America’s first golden era of technology. At twenty, he founded a coking company in the tech center of the day, Pittsburgh. Coke, “distilled” coal, burns hotter and cleaner, perfect for forging steel. Frick soon partnered with Andrew Carnegie, later, the two of them with the help of financier JP Morgan created US Steel, the first major corporate conglomerate. How civilized any such conglomerates can be is questionable, from any sort of civilized democratic perspective, not at all.

In the history of US labor, for those who know such things, Frick’s name is rather infamous. In 1892, at Frick’s and Carnegie’s Homestead Steel plant, Frick hired a three-hundred man armed force of Pinkerton private police to disrupt one of industrial labor’s early strikes. With ten strikers killed, the republic’s civil veneer was not scratched but gashed. The strikers beat back the Pinkerton thugs, but the Pennsylvania Governor soon after provided several thousand national guard troops to oust the strikers and place Frick back in control – call it industrial rule, the agrarian republic never stood a chance.

There’s no portrait of dead steel workers at Frick’s museum. While the collection is impressive, it leaves the feeling of a cultural wannabe, a backwoods nouveau riche buying faux-aristocratic prestige. Most curious and in ways telling is the lack of representation of the great revolution of art, starting with Impressionism, that occurred over the last forty years of Frick’s life. Fascinatingly, he has a couple early, bright, clear paintings of JW Turner, whose later infatuation with the steam produced by England’s burgeoning coal-fired industrial engines greatly influence the Impressionist painters that followed. Could Frick not face what his industrial revolution unleashed? Was industrialism's very soul uncivilized?

Secondly, reading Harriet Flowers, Roman Republics also had me considering civilization. One thing, most civil adequacy usually goes right out the door on any civilization's frontier. At best, civil adequacy is always an internal feature. This is particularly true regarding the democratic politics of the Roman republic. What seems quite incredible is for over three centuries, as the republic fought endlessly with its neighbors, conquering much of the land touching the Mediterranean, there was simultaneously no violence in settling the political matters between Rome's citizenry – call it republican civilization, much more profound than a veneer.

However, in the last century, as the republic collapsed, violence became the norm. Flowers retells the story of how Tiberius Gracchus, advocating then desperately needed political and economic reform, was assassinated in the Forum. He was killed by the pontiff maximus, Rome’s greatest priest, on the stairs of Jupiter’s Temple. The temple had been erected at the republic’s founding. Now there’s a political act of violence drowning in symbolism. Gracchus' assassination initiated a cascade of political violence that wouldn’t stop for another century with the end of the republic and the beginning of the imperial rule instituted by Augustus, a thin veneer of civilization restored.

Flowers’ description of how this one event instigated an unending downward republican spiral is excellent:

“In fact, it must be stressed that this violence was much more corrosive of republican political values and practices than has usually been admitted. In political terms any violence was in itself a basic breach of republican principles. The use of force constituted an admission, or perhaps often an assertion, of the failure of the accepted political system to resolve conflict or even to manage some of the regular functions of government. As soon as such a failure occurred or was claimed to have occurred, it inevitably weakened republican norms, and at the same time a further precedent for violent behavior was being set. Moreover, these political effects came on top of the inevitable cycle of revenge that was unleashed by any killings. All this was much more serious in a city-state that claimed to have solved the problem of societal strife and class warfare long ago by developing a community based on the equal access of all citizens to a law code regulated by a jury court system.”

In regards to keeping violence out of politics, the US never quite reached Rome’s civil heights. Today, it is clear our politics are increasingly incapable of “resolving conflict" and failing in "managing the regular functions of government.” We witness the American political class enthralled by a degenerate tit for tat race to the bottom with fraudulent lawsuits, foreign conspiracies, election denials, redistricting cleverness, and a decades long overreaching of executive power, most recently egregiously represented by federal armed forces, such as ICE and the military, occupying cities. All are precedents catalyzing an ever rapid spiraling of the drain. History shows removing any civilization’s veneer leaves nothing but sorrow, tears, and blood for all.