Democracy, Organization, Violence: Lessons From the Civil Rights Movement

“In order for us as poor and oppressed people to become a part of a society that is meaningful, the system under which we now exist has to be radically changed. This means that we are going to have to learn to think in radical terms. I use the term radical in its original meaning—getting down to and understanding the root cause. It means facing a system that does not lend itself to your needs and devising means by which you change that system.” - Ella Baker, 1969

Historically, it appears ever more clearly the Civil Rights Movement was the last push for democracy in America. It was the most rarefied and deepest democratic politics. Each time you dig into its history, you learn more. The Movement created an astoundingly imaginative environment, a flowering of democratic thinking unmatched in American history. It’s uncertain how exactly such eras of political creativity arise and flourish. Wrong to think of them as a chance gathering of extraordinary individuals, better conceived as a collective coming together in a specific time and space necessitating and facilitating imaginative thinking among all involved.

Over the years, the Civil Rights Movement has been emasculated by exclusive association with one man, Dr. King. This is in no way a slight to Dr. King, one of the important figures of the 20th century, but focus on one man, and worse one part of his message completely loses the substance of the Movement itself, along with any understanding of how it moved. King’s deification ignores the the hundreds of thousands who actually defined the Movement, lost is any ability for the future to understand how it actually manifested, helping assure it doesn't happen again. Perceiving exclusively through King, what is essentially missed is the Movement's organization, without organization there was no movement. It is analogous to politics in America today where the concepts, processes, and structures of democratic organization barely exist or atrophied to impotence, the only focus on flawed personalities.

Pulling one thread of the great quilt that was the Movement's structure, a thread organizationally weaved across its length and breadth is the beautiful democrat Ella Baker, providing much greater organizational insight than Dr. King. In her book Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision, Barbara Ransby writes of Baker's first political organizing experience in 1930, “Baker took on a role she continued to play for much of her political life, that of a behind-the-scenes organizer who paid attention to the mechanics of movement building in a way that few high-profile charismatic leaders did, or even knew how to do.”

Ella Baker was raised in a small town in North Carolina, graduated from Shaw University, and moved to New York in the late 1920s, right before the Depression began. She was taken by the great flowering of African American culture in Harlem, “a hot bed of radical thinking.” She absorbed every aspect of the intellectual milieu. Having to feed body and soul, she worked all sorts of laboring occupations. In 1930, at the Depression's depths she began organizing with the Young Negroes Cooperative League (YNCL).

“In lauding Baker's credentials in a 1932 article in the NAACP's magazine, the Crisis, her mentor, George Schuyler (YNCL), underscored the learning process that occurred through Baker's participation in the low-wage work force. “By force of circumstances,” he observed, “her ‘post graduate’ work has included domestic service, factory work and other freelance labors, to which ‘courses’ she credits her education.” (Ransby)

Baker soon understood economic organization in America was overwhelmingly concentrated in the corporation. At this point, labor was attempting what would eventually be a futile effort to catch-up, while the final factor in the economic equation, the consumer, was complete entropy. She wrote at the time,

“All work is but a means to the end of meeting consumer demands. The ‘real wage’ is what the pay envelope will actually buy. The wage-earner's well-being is determined as much at the points of distribution and consumption as at the point of production… . Since recurrent ‘business slumps’ and the increased mechanization of industry tend to decrease the primal importance of the worker as producer, he must be oriented to the increasingly more important role of consumer.” (Ransby)

Baker understood production, distribution, and consumption were all economic elements needing to be democratically organized. All power, whether social, political, or economic is organized, this organization defines power. Organization is the fundamental element of all politics, key to all democracy. Economically, America was, and still is, in need of a reorganization of production, distribution and consumption. Ransby astutely and succinctly sums up,

“Baker's political philosophy called for challenging the laws and institutions of society in order to eliminate discrimination and inequity, but at the same time she felt strongly that any movement for social change must transform the individuals involved― their values, priorities, and modes of personal interaction. Baker expressed this viewpoint as early as the 1940s, and it remained a constant theme in her politics thereafter. The cooperative movement offered organizers a way of working with people on a protracted, day-to-day basis. The process of setting up co-ops, establishing common priorities for those involved, solidifying democratic methods of decision making, and building communications networks encouraged people at the grassroots to engage in social change and transformation, changing themselves, each other, and the world around them simultaneously. Unlike such singular events as voting on election day or attending a political rally, involvement in cooperatives and buying clubs enabled people to redefine the ways in which they related to neighbors, friends, and co-workers. For Baker, political struggle was, above all, a process, and she insisted that the structure of political organizations had to allow for the process of personal and political transformation to occur.”

Starting in 1938, she worked for the NAACP for 15 years, becoming one of their most important organizers, helping establish chapters across the South. In 1957, she attended the meeting that founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which grew out of Montgomery Bus Boycotts. Dr. King was SCLC’s first president, Baker their first director. She chafed in the environment, the Conference was largely comprised of male preachers, King the charismatic head. It was not the bottom-up organization Baker understood democratically essential.

In 1960, she left SCLC and at her alma mater, Shaw University, formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Black students across the South had been organizing against segregated public facilities. SNCC gave them a structure, a distributed structure, allowing them to communicate, plan, and share resources. SNCC quickly turned its attention to registering Blacks across the South to vote so they might be able to start wielding government power.

Life in the 21st Century is a reader-supported publication. Please become a paid subscriber.

SNCC would provide some of the greatest organizational efforts of the 1960s, two included the efforts of organizer Stokely Carmichael. The first was in the Mississippi Delta, out of which came the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. They went to the 1964 Democratic convention to be seated in place of the established segregated White Mississippi party structure. The Democratic convention refused to seat them, keeping the all White delegation.

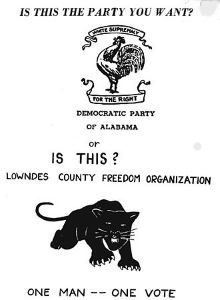

Learning from this, Carmichael went to Lowndes County, Alabama to help organize voter registration and voters. Lowndes County was located between Montgomery and Selma. It's population was 80% Black, yet no Blacks held any elected office. Learning from the Mississippi effort, SNCC worked with John Hulett, forming the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) as an alternative to the Democratic party. Along with being politically disenfranchised and economically enslaved, most of the residents of Lowndes were illiterate, so a SNCC staffer developed a black panther as its ballot symbol.

Lowndes County is an important event in the evolution of the Civil Rights Movement, in certain ways its pinnacle, but two important changes signaled its dissolution. First was the end of the exclusivity of non-violence as a confrontational tactic, with Carmichael raising the option of violence as a defensive stand. SNCC brought down armed urban youths from the North as guards against long established White terror tactics. Though in this interview, Carmichael talks of the fifty and sixty year old Lowndes County residents impressing the Northern youths. Many of the residents had guns, which they brought to the polls but left outside before voting. Such an essential fact is helpful in any attempt to understand American gun culture, such at this point it can be understood at all, but it reaches back very far, goes very deep, and is spread across race, gender, and class.

The second aspect of change occurring at the time of Lowndes was a shift of focus to Black Nationalism or Black Power. It was not in direct opposition to the Movement's message, but very much an important tactical shift. Prior to this, the Movement's message was enfranchising the descendants of American slavery into the greater political system by breaking the walls of segregation imposed across society. It was a bringing together. Focus on Black Power was perceived, not necessarily accurately, as separation.

Across the South, African Americans were as economically disenfranchised as politically. Most didn't own land, they were sharecroppers or at the bottom of the labor heap. Money earned would largely end up in the pockets of Whites outside the community. Certainly there was merit to organize the Black community economically and to elect people to office, in fact it was a necessity. Nonetheless for a minority population to do this in a larger, hostile majority economic and political cultures, required politics of the highest order.

The slogan of Black Power proved especially seductive among the North's urban youth, who while not facing the codified segregation of the South, faced plenty social, economic, and cultural segregation. Black Nationalism was a long held idea in the community from Marcus Garvey to the recently assassinated Malcolm X. Back earlier in the century, “In a series of articles in the Pittsburgh Courier, W.E.B. Du Bois explained that the entire working class could ‘make one assault upon poverty and race hate.’ But to begin this process, black Americans had to build their own separate organizations along cooperative lines. Du Bois held the view that “the rise of black cooperativism would ultimately establish a unity between workers of both races.'” (Ransby)

Ella Baker wrote in the 1940s, which just as well could have been advise to the 1960s Black Power advocates,

“I could but think ‘how true and yet how false.’ True that a new economic order must be built, but false to hope that it can be built by the Negro alone on any policy of racial isolation. True that the Negro's future will be determined by his own efforts, but false to expect … that it can be achieved by … racial isolation. While we are tugging at our own bootstraps, we must realize that our interests are more often than not identical to that of others. We must recognize the identity of interests, work with other groups … [and yet not sacrifice our interests to that of the larger cause]. A difficult but unavoidable task.”

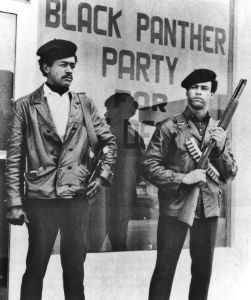

A difficult but unavoidable task indeed. Black Power was quickly adopted by the newly formed Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland, California. The Panthers borrowed their symbol from the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, but never lasted long enough to effectively organize. Their initial organizational efforts focused around providing breakfasts for children and notoriously as armed patrols patrolling an Oakland police force known for brutality. They didn't have to show up to too many places armed and patrolling the police to quickly gain notoriety. (Bobby Seale, one of the party's founders, gives an excellent account of the Panthers and his life, a quintessential American democratic life.)

When the Panther's were established it was legal to carry a loaded, unconcealed weapon in California. The Panthers’ patrols produced immediate reaction. A Republican legislator with the support of the NRA created legislation, soon to be signed by Governor Ronald Reagan, outlawing the public from carrying loaded guns. In opposition to the bill, two dozen gun-toting Panthers showed up at the Capitol in Sacramento, gaining the Panthers not just national, but as Seale points out, instantaneous international attention for an organization that at that point didn't have more than a hundred members.

If I know one thing about America, you don't want to scare the Whites against you, unfortunately they scare very easily. Across the country, the Panthers were quickly harassed, jailed, and murdered by police forces and the FBI. It can be said with their end, the Civil Rights Movement ended. Just as from the movement it sprung, the Panthers talked a lot about education and organizing, but they had no time. They were first and foremost a Warholian media creation. The Movement had always been astute at using broadcast media, most graphically with images of their bloody busted heads and attacks by trained police dogs. But American broadcast media, was always undemocratically structured, controlled by a handful of corporations. The Panthers quickly exploited the new media power, but they failed to understand its power resided in a very undemocratic, centralized technological architecture.

A movement started by and succeeding through the determinedly grounded, long, hard work of person to person, nonviolent organizing, ended as an ephemeral symbol of violence in the aerial waves of broadcast media. Yet, it would be this media event/personality politics that came to completely define American political discourse over the following decades, actual democratic organizing a lost and forgotten art.

Ironically, or maybe not, comprised of a largely disenfranchised people, the Civil Rights Movement had astute democratic understanding and practice. It held up a mirror to American political culture revealing its shortcomings, its ugliness, and challenged Americans to become the democracy they claimed to be. The Movements' organizing efforts became the last attempt at renewing the processes of the republic's structure as it existed. Unfortunately, the American industrial economy had peaked in wealth creation just as the majority of African Americans became politically enfranchised. The bottom of the wage-pool was about to be continuously flooded by Americans of all ethnicities sinking from above, an undertow easily manipulated by a failing and increasingly degenerate political process.

The Panther's 10-Point Plan ended with the first two paragraphs of the Declaration of Independence and includes a list of political and economic demands, summed up in the last point, “We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice, peace and people’s community control of modern technology.” Incredibly, the control of modern technology as a democratic political issue never reappeared despite technology' ever greater role in shaping the economy, politics, and culture. In their thinking about economic concerns, Black Power and the Panthers descended into the vast void of non-democratic Marxist rhetoric. A half-century later, the world remains bereft of desperately needed new thinking on economic organization. Maybe it can be catalyzed by banning the words capitalism and socialism, forcing people to begin talking about actual structures and processes?

Dr. King had come to the same conclusion regarding the newly politically enfranchised though economically disenfranchised. Neither embracing nor opposing Black Power, King launched “The Poor People's Campaign,” seeking to unite America's economic bottom. This campaign was cut short by a bullet shattering King's face on that Memphis hotel balcony. A man who peacefully helped create one of the great democratic movements in history dispensed by a single the bullet, no greater example of violence’s tyranny.

King's stand on violence is why he should really be remembered. It is not a coincidence 20th century mass violence resulted in the creation of history's greatest non-violent figures, including King, Gandhi, Gorbachev, Mandela, and Einstein. The first two correctly understood democracy as a nonviolent process, persuasively revealing the violence necessary for both segregation and colonialism. Upon reaching power, Mandela refused retaliation against his former oppressors. Gorbachev, unique to history, refused the use of violence to keep together an empire created by violence. Einstein warned technological development had made political violence against humanity’s self-interest, suicidal.

At the end of the Civil Rights Movement, the American empire intruded ever more abusively into politics. The numbers of African American military draftees far outnumbered their population numbers. One of the Panthers’ 10 points was “We want an immediate end to all wars of aggression.” What does that say about today when a recent Wall Street Journal article is titled, “A Guide to the Middle East’s Growing Conflicts, in Six Maps.”

The Civil Rights Movement is one of history's greatest lessons in democracy. Several components were advocated by all involved and upheld as democratic necessity:

- Education is the first task of every organizer — the Jeffersonian democratic imperative that knowledge is essential for the entire citizenry.

- Organizers bring people together to talk as equals. It is in meeting as equals where democracy becomes a creative force.

- Violence is the antithesis of democracy, any system held together by violence is inherently undemocratic.

However, the most important lesson of the Civil Rights Movement is understanding that societal organization, its structures are power. All democracy requires understanding of social, political and economic organization. Today, reforming government, political, economic, and technological organization is a democratic necessity. The pernicious politics of today’s America starts with the unchallenged acceptance of our existing archaic, undemocratic institutions and processes.

Ella Baker understood educating and organizing people to come together, meet, discuss, and then act were essential elements of all democratic politics — the core of the politics of the Civil Rights Movement. Today, it is forgotten. The most important reason for this is technology, which has rewired society against healthy political interaction, resulting in control residing in ever fewer hands. A radical, to the root, necessary rethinking of democracy needs to include an understanding of the role of technology, its architecture, how it is controlled. If technologies do not have a democratic architecture, no democracy can be built through them. Just as for centuries, African American disenfranchisement was not an accident, it is not an accident democracy has disappeared from America today, a most anti-Baker willful ignorance a prime culprit.