Empires of the Steppes

Life in the 21st Century is a reader-supported publication. Please consider become a paid subscriber.

From our beginnings, Homo sapiens have been a migratory species. Only in the last ten thousand years, with the dawn of agriculture, has humanity become relatively sedentary. However, even across these ten thousand years, migration remained a continuing endeavor across the globe. Great populations of migratory hunter-gatherers continued to trek as farming culture took root, while many peoples in the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Europe undertaking animal husbandry, also adopted their herds migratory ways. Kenneth Harl's Empires of the Steppes: A History of the Nomadic Tribes Who Shaped Civilization is the stories of the peoples who inhabited the vast Eurasian steppes and for several thousand years shaped the histories of China, India, the Middle East, and Europe.

Empires of the Steppes is a dense, well written book. It's difficult if not impossible to write good history without a certain thickness. Written well, each sentence becomes a thread knitting a complex storied quilt of the past. Insights gained are not only the greater woven mosaic, but individual threads, a single sentence can provide key understanding of history's complex design. The avoidance of history by most is both perplexing and disappointing. History offers understanding of how we've come to where we are by descriptions of indeterminate, contingent currents. The worst historians present the human story as a deterministic straightjacket, instead of providing a service as a type of ancient kybernetes, a helpful steersman across the turbulent, chaotic ocean upon which all life is adrift. For thousands of years, humanity knew no greater ocean than the grasslands of the Eurasian steppes.

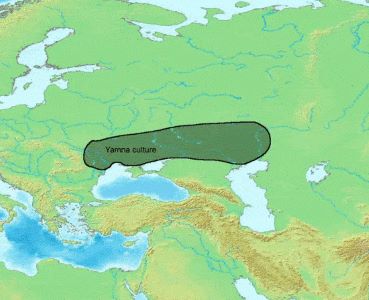

Empires of the Steppes begins five thousand years ago with the story of the Yamnaya culture, which thrived above the Black and Caspian Seas – present day Ukraine, Russia, and Kazakhstan. These peoples were not the ancestors of the Rus, Slavs, and others who claim the land today. They were the culture that produced the roots of Indo-European languages — Greek, Sanskrit, Early Germanic, Old Irish, and directly related Indo-Iranian, — such is the long cultural impact of these western steppes peoples.

The influence of the steppes was never in one direction, traditionally held as east to west, but instead more of a whirlpool, with currents moving in different directions toward one region and then back again. A good example is the Tocharian, who over tens of centuries moved from the Yamnaya area east to Siberia, then back west and south to the Tarim Basin. They were not the present Uygur inhabitants, who are Turks. Established there, the Tocharian held Buddhist beliefs initiated in India, which in part was influenced by other east and south bound Yamnaya migrants who ended up crossing the Hindu Kush. From the beginning, the flow of people and culture across the steppes was multi-directional.

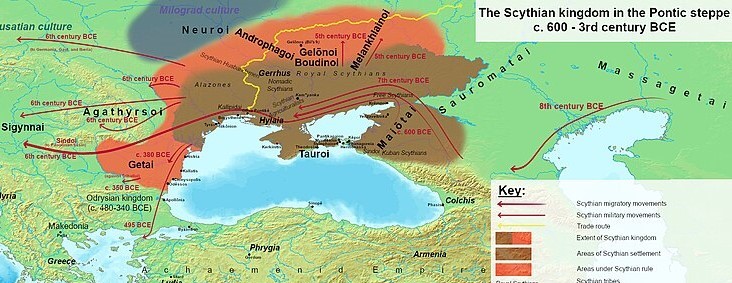

The first of the steppes people to be recorded by the West, by the Greeks, was the great empire of the Scythians, who were pushed west from the Central steppes, ending up roughly in the Yamnaya region two thousand years later. The Scythians are mentioned by the Greek historian Herodotus and originated the idea of the Amazon woman warrior. Anacharsis, a Scythian philosopher, made his way to Athens and offered one of the greatest critiques of Solon's constitution, ”a spider's web that ensnared the weak, but was easily ripped up by the rich” — an astute observation by a “barbarian,” no better critique could be written today of its American constitutional descendant.

The Scythians were gradually overrun by the Goths, who for the last centuries of Rome continually harassed and eventually overran the eternal city. I wrote about the Huns here, who first pushed the Goths from the steppes into the Roman empire, eventually ending Rome's long rule.

With Alexander's push east, the steppes and Greeks became more enmeshed. “By the opening of the second century BC, as the cultural and commercial ties between the Western and Central Eurasian steppes and the urban Hellenistic world had become so intertwined that the two worlds came to depend on each other in what has been dubbed the first era of a global economy.”

On the other side of the steppes, with the beginning of China's first great dynasty the Qin, the Chinese encountered the Xiongnu (fierce slave). Against these people the Great Wall was first erected. The Xiongnu created the steppes' first vast empire, stretching from modern Manchuria west to almost the Caspian Sea. For centuries the Chinese and Xiongnu would be both at war and peacefully entwined. In the first century, the Han Dynasty established Chinese dominance.

East or west, the nomadic peoples of the steppes differed from the sedentary farming cultures they encountered whether Chinese, Greek, Vedic, or Assyrian. Their shelters were mobile, moving with their herds across the steppes' ocean of grass. Proficiency at cavalry warfare based on their horse and archery skills gave them continual victories against the established agrarian, largely infantry armies. No better example was provided by the Roman Consul Crassus’ great defeat against the Parthians, who had rode from the steppes and established an empire stretching from Mesopotamia to the Indus. Crassus was lured by the Parthians, a favored tactic, into battle near modern Harran, Turkey. The Parthians expert horsemanship included the skill of shooting backwards as accurately as forward and they rained a seemingly inexhaustible supply of arrows on top the Roman Legion. The Battle of Carrhae was considered one of the republic's greatest military defeats in five centuries.

It was this specific brilliance in military matters that made the empires of the steppes such formidable opponents. Their innovations of saddles, stirrups, and wheeled chariots facilitated their thousand and half year march across the steppes to southern China, Delhi, the Mesopotamian, Rome, Kiev, and finally Constantinople. Innumerous peoples of “unrelated families, clans, or tribes shared the same steppes according to customary arrangements. Nomads evolved rules of hospitality so vital for survival for all. Hosts granted permission to neighbors or newcomers the right of passage over ancestral grasslands.” Another shared cultural identity was belief in the god of the great open sky, Tengri, allowing a certain easy adaptability of the Abrahamic religions, Buddhism, and Tian, the great Chinese heaven, which itself might be an early influence from the steppes.

To the Western mind, the two great peoples of the steppes are the Turks and Mongols, both emanating from the Central East Asian steppes. The Turks were first, coming from somewhere around the Altai mountains. Harl writes,

“The Turkish languages today, classified as a branch of the Altaic language family, might have emerged in the first century BC, but its earliest written records are the inscriptions of the Orkhon valley (Mongolia) eight centuries later. … All five modern branches of Turkish can be traced back to the language of the Orkhon inscriptions nearly thirteen centuries earlier.”

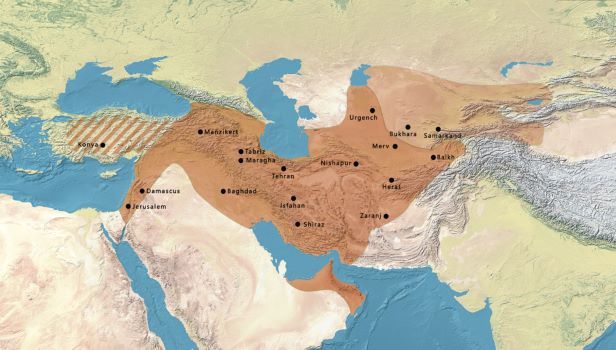

Interestingly, the Turks introduction to the West came from the Arabs. Two centuries after the fall of Rome, the Arabs zealously crusaded out of the desert, in a matter of decades conquering from Spain to the Indus, while pushing above Iran into the Asian steppes then occupied by the Turks. Centuries later, the Turks came to Byzantium not under the shield of Tengri but the sword of Allah. By the 11th century, the Seljuk Empire extended east from Jerusalem to across modern Turkmenistan and Afghanistan. Yet it would take another four centuries for the Ottoman Turks to finally conquer Constantinople, which proved so intractable the Ottomans moved around Imperial Rome's final capital to first conquer the Balkans to the Danube, fighting previous steppe tribes like the Bulgars and Huns who had centuries previously settled and assimilated. With Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire, extending at its height across North Africa, survived until World War I.

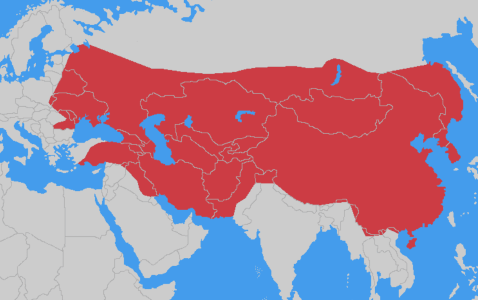

Nonetheless of all the peoples of the steppes, the Mongols still best hold the contemporary imagination, not without reason. In a matter of decades, the empire launched by Genghis Khan spread from the Pacific Coast to Kiev, most of China, and the Middle East from the Tigris to the Indus. It would be largest contiguous empire in history. “Most likely, three-quarters of the warriors who loyally followed Genghis Khan were Turkish rather than Mongolian speakers.”

For a century, the Mongols ruled China under the Yuan Dynasty, riding into Europe all the way to Budapest before just as quickly withdrawing due to a succession battle back in Karakorum. Harl also suggests Mongol scouts at the end of Hungarian plain, the far west Eurasian steppes, realized they'd be at a loss for fodder for their vast herds. Mongols had as many as ten mounts for each warrior.

Most perversely still etched in the European imagination is the Mongol conquest of Russia by Genghis' grandson Batu, imprinted on Russian memory as the Tartar Yoke.

“In just four years, Batu had conquered the principalities of Orthodox Russia, and for the next three centuries, Russian princes saluted Batu and his heirs as Tsar, the Slavic for Caesar, and so the secular lord of the Orthodox world. Batu significantly contributed to forging the future ideology and institutions of autocratic Russia. The Russians princes, long in awe of the power of the Tartar Khan at Saray, fused Mongol ritual and institutions of those of Byzantine heritage. Batu also unwittingly shifted the political axis from Kiev to Moscow. The Grand Princes of Muscovy steadily extended their political influence because they dutifully acted as the revenue agents who collected and delivered the tribute that the Russians owed to Batu's heirs.”

So much in this paragraph, starting with the long established and still complexly intertwined existences of Moscow and Kiev, both originally founded by the Rus from northwest Europe. Amusingly, Moscow's perceived initial and some would say still long established parasitic role in Russia. And finally, though it is without contention the Mongols greatly influenced Russian history, to blame Russia's history of autocracy on the Mongols isn't just a stretch, but propagating a long practiced tradition of prejudice against the East. Neither Russian or any other European monarchies needed any education in strong arm rule of the few over the many, the capability to wield brutality. The Russians still fault the Mongols for many things, while the rest of Europe's cockeyed fear of Russia has long ago roots stretching back to the the great Khans and still imagined hordes just below the horizon ready to assault, despite the fact in the centuries following the Ruskis loosening the Tartar Yoke, it would be the Poles, Swedes, French and Germans all marching east into Russia.

In the 14th century, the last great march from the steppes began in present day Uzbekistan, led by the Turk/Mongol descended Timur. “The Sword of Islam” emerged from the now largely Muslim Central steppes, battling from Anatolia to Europe, China, and India, where he sacked the Delhi Sultanate. A century later, his descendant Babur would establish India's Mughal Dynasty, leaving behind the grand Taj Mahal.

After Babur, the great waves of people from the Eurasian grasslands diminished in power and strength. Instead of rising across the steppes, the next great global empires rose across the oceans. The Eurasian steppes influence ended as Portugal, Spain, England et al. sailed the seas with innovative ships, guns, and cannons. Their horses sailed too. These empires stretched around the planet, including the Americas and Australia, though any attempts of Europe to gain hold of the Eurasian steppes never went far, best exemplified by the Brits crossing the Hindu Kush and the most recent Unites States' Afghanistan fiasco.

Harl's book is an excellent piece of history about a massive region of the planet that for thousands of years from the Yamnaya of the Western steppes to the Mongols of the East helped shaped the world of today. Nonetheless, in the long history of Homo sapiens, it is a small snapshot in time of a species that has been in constant motion since rising on two legs, moving around and then out of Africa. Only in the last ten thousand years with the rise of farming have we've grown more, though certainly by no means completely sedentary. Most of the great migrations of the last two centuries have been out of Europe and Africa into the Americas. It makes one ponder what Europe and the world would look like today if there hadn't been the great expanse of the Americas to receive Europe’s hordes.

We are entering a new era of mass migration from the planet's south to the planet’s north, pushed not by other peoples, but environmental and economic forces – the two should by no means be considered separate. It needs to be stressed most of the economic and environmental migration catalysts were overwhelmingly innovated and manufactured in the last two centuries by the global North. It is a mass migration occurring with the establishment in the last century, or at most two, of largely arbitrary national borders. It is also the first migration to occur with the still not quite well grasped understanding of humanity as one biological species, a paramount identity despite whatever cultural differences placed atop that developed by thousands of years of geographic separation. The economic and environmental challenges we face are not those of one group of people, one nation, but concern the common wants and needs that make us all human, all sharing a very small planet. No one’s walking, riding, sailing, of flying anywhere else.