Evolving Democracy: The Courts

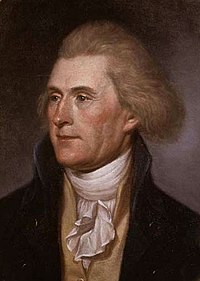

"It has long been my opinion, and I have never shrunk from its expression,... that the germ of dissolution of our Federal Government is in the constitution of the Federal Judiciary--an irresponsible body (for impeachment is scarcely a scare-crow), working like gravity by night and by day, gaining a little today and a little tomorrow, and advancing its noiseless step like a thief over the field of jurisdiction until all shall be usurped from the States and the government be consolidated into one. To this I am opposed." - Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Charles Hammond, 1821

Ironically, Jefferson endures as one of the greatest critics of the American institutions he helped birth. His critiques almost always emanate from a democratic politics, in opposition to institutions taking power away from the greater population where power rightfully resided. Unbeknownst to Jefferson's legion of contemporary foes, across most of American history Jefferson was ostracized for his democratic thinking.

Little is remembered of Jefferson's warnings on the growing unchecked power of the federal courts. However, two-hundred years later, a contemporary Jeffersonian writes a little noticed book that includes an excellent chapter on the power of our now undemocratic and completely entrenched federal courts. Attorney Thomas Geoghegan's, The History of Democracy Has Yet to Be Written has an excellent critique of oligarchical governance by our federal courts. Geoghegan writes, “The federal courts do the governing of the world: intellectual property, labor, speech, police, race, corporate deals, everything, everything, and everything.”

He polemically and beautifully indicts,

“The US Supreme Court distracts us from this real deep state; it even distracts many sensible pundits. It distracts us from the real way we are being governed. Watching the US Supreme Court as we do is like watching episodes of “The Crown,” inasmuch as it helps anyone understand the real way the country is governed. It is a mistake just to focus on the court, or who is on it, just as it is a mistake to think that Washington, DC, exists only or even mostly within DC. The real Washington, DC, is just as much out here, in St. Louis or Phoenix or Miami, where the federal judges sit, as the real Roman Empire was in the provincial cities where its proconsuls were. Except under our form of government, these proconsuls serve for life, and we are not nearly as good as the Antonine emperors in keeping track of them. There may be quality control, of a kind, at the time of confirmation, but then that quality control stops for the next thirty or forty years.”

“A quality control, of a kind” existing at all through the Congress is debatable. With a completely debauched and corrupted political system, quality of any sort has little to nothing to do with any of it. Tom adds, “All these lower federal courts collectively have far more power than the US Supreme Court or federal agencies―and if I could choose, I’d rather appoint all the district and appellate court judges in this country.”

Geoghegan correctly looks at our archaic institutions of government, the system Jefferson and his cohorts bequeathed to us as the source of the problem. He writes,

“While the judiciary may look like the weakest branch, and purports to defer to Congress, the entire lower bench as a body is much more capable at governing than the US House, which, thanks to the Senate, is often incapable of governing at all. In an antitrust case, a single federal judge can decide, as the US House cannot, how much power a company like Google can exercise over the land.”

Beside the judiciary sits a modern priesthood, the attorneys, secularly ordained intermediaries between the citizenry and the courts. Remember a few years back, lawyers were the butt of jokes about unaccountable, shyster power. Then came 2008. Americans re-awoke to the bankers’ filthy lucre, lawyers sort of faded into the background. Attorney Geoghegan reminds us,

“Yet who has even more power in our republic than all these lower court federal judges? We lawyers do. Because we lawyers decide what cases they

are forced to hear. ...lawyers have incredible power to pull you in to have

your deposition for three hours under oath; we have the power to make you recover from your hard drive all those documents you tried to delete the night before we sued you. If that is not a license to kill, it is at least a license to break and enter. It is the right―in a pretrial period that may last for years―to poke through your house, or your business, and ask what you have in that drawer, or over in that box, and while this poking around goes on for years, the judges who have the case may only check in occasionally to see what is going on.”

Tom's democratic solution is inarguably a necessary restructuring of the federal system. He writes, “The court seems like an alternative to representative government, it’s only because representative government, under our Constitution, is not a viable alternative in the first place.”

Here, he correctly points to a major part of the problem – the Senate, “With too many vetoes, too many senators who, representing as few as 8 percent

of the electorate, can stop a law.” He calls for the Senate's abolition leaving the Congress as a single assembly, “If Congress were really the People’s House, we would feel less need to pack the court, because the court would be less important.”

Having with Tom, long ago advocated the abolition of the Senate, such reform is entirely too radical for our depraved political class to contemplate. Much more distressing, any real ideas of reform are completely absent from the collective or even the individual minds of the American people, who from birth are instilled with reverence for, though provided little understanding of, a constitution that today is used to politically disenfranchise them more than liberate.

It is the great political paradox of this era where the majority of Americans grow ever more alienated from their institutions, ideas for reforming them remain nonexistent. While Geoghegan is spot on identifying one important problem, his reform, though radical to many, remains nestled in the original government structure. A structure completely shaped by the Agrarian Era from which it sprouted, but was then supplanted by industrialism, and now hapless in a burgeoning new technological era.

It is forgotten, except when convenient for various varieties of political Neanderthals, not that I have anything against Neanderthals though the best are long extinct, the constitution was originally (I used the word intentionally for our constitutional scholars) based on the literal uniting of the states. “In order to form a more perfect union” between the states, the constitution was unanimously ratified by the states. The constitution establishes the Senate as the states institutional power in the Federal Government. At the top of this piece, Jefferson laments the federal courts usurping the power of the states.

At the founding, all but the most zealous Federalists looked at the states as the greatest check and balance on federal power. In the newly formed District of Columbia, arguing about the states' power — “state's rights” — was prominent on many tongues, eventually growing everlastingly tarnished as the main constitutional defense of slavery.

Mr. Lincoln bloodily deconstructed this defense. After the decisive victory of Mr. Lincoln's bellicose argument, DC became unchecked sovereign. Over the decades following, the courts played a crucial role codifying DC's dominance, wielding the Interstate Commerce Clause among various other imaginative interpretations of the constitution.

As representatives of the states, the Senate is basically an unneeded anachronism. From the beginning, a check on democracy, Geoghegan correctly defines today's Senate not as a check or balance, but a democratic obstruction. Today's Senate doesn't even represent the states, it is the ruling corporatocracy's greatest lever of power. Ridding DC of the Senate would certainly make the House more powerful. However, would it result in a more representative system? This is debatable, starting with the simple fact 435 people can in no way represent 350 million, not even considering the deplorable condition of the rest of the American political process.

A more constructive way to approach reform would be to turn our present way of looking at politics on its head, breaking the confines of our two-hundred and fifty year old governing architecture by restructuring from the ground up, using Jefferson's concept of self-government instituted through ward-republics as a guide. With regards to self-government, the essential questions are how decisions get made and who makes them. Geoghegan makes the incontrovertible case that decision making today is done largely by the federal courts, little about it democratic. A logical reform question follows, how can the courts be democratized?

One cause of the courts present preeminence was industrialization. Daily-life became not simply influenced, but decisively shaped by forces beyond the forces of the immediate locality of a farming society. With industrialization, life, not just labor became increasingly divided. This division impacted every aspect of life, including or maybe most especially knowledge. Industrial value, as Adam Smith noted, was gained through specialization.

The courts specialize in “law,” but law's whole purpose is generalization across specialization. Judges have little or no knowledge of the concerns of most specialized fields placed before them. They are expected to learn, how well is another question, the intricacies of any given case placed before them. It is the attorneys' role to be the educator. This understanding of court processes can provide the basis for reform in a new era.

With industrialization, the courts' role became increasingly defined by the accompanying massive growth of information. Today, information growth exponentially increases with the proliferation of new information technologies. Over a half-century ago, physicist and atomic bomb innovator, J. Robert Oppenheimer, astutely pointed to the problems facing governance from the exponential growth of science, technology, and the resultant explosion of information, stating,

“We face our new problems, created by the practical consequences of technology and the vast intellectual consequences of science itself, in a context of two or three billion people, in the context of an enormous society, in a context of a society for which none of our institutions were ever really designed.”

Today, it is in a context of eight billion people. Our unchanged institutions even more incapable of dealing with science, technology and exponential information growth. From a constitutional perspective, it is ludicrous to believe one person in the presidency could in anyway constructively meet this information tsunami, yet the vast majority of our so-called politics is centered on who this hapless person will be. Nor can it be argued is a pre-industrial Congress any better equipped. Across the industrial era, history chronicles government constantly reacting to, rarely in congress, or ahead of technological development. In dealing with the onslaught of change, the greatest burden was placed on the courts.

If restructured, courts could play a healthy democratic role with the understanding the massive amount of information being produced to be democratically useful must be continuously edited, processed, and decided on. It is a role the present courts already play. They can be democratically restructured using an equivalent of the jury system, with the citizenry enfranchised to decide how decisions are made.

Doing this requires a restating and evolving the role of the citizen. Instead of the judges and attorneys being the only enfranchised generalists, it can be a role embraced by the citizenry. Just as today, the judge is expected to learn the general and particulars of each case, so too would the reform jurors, randomly chosen for each case and compensated accordingly for time and effort.

The great Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis wrote,

“My early associations were such as to give me greater reverence than I now have for the things that are because they are. I recall that when I began to practice law I thought it awkward, stupid, and vulgar that a jury of twelve inexpert men should have the power to decide. I had the greatest respect for the judge. I trusted only expert opinion. Experience of life has made me democratic. I began to see that many things sanctioned by expert opinion and denounced by popular opinion were wrong.”

This is a major problem for the 21st century, expert opinion may not simply be wrong, but entrenched in all sort of ways, processes, institutions, and maybe most detrimentally in simple habit, sheltered from alteration, whether by legislation, the courts, or public necessity. Every specialization creates its own priesthood, people with a deep understanding of a specific topic, issue, or entire school of thought, who deal only with each other, creating language only they understand.

Certainly this specialization, this division of intellect proved important, valuable, and necessary for the progress of science. And that there's no way to really change this particularly, though there's a definite existential need for greater popular understanding of science as a whole to foster a truly constructive and healthy politics for the 21st century and beyond.

Specialization proves especially detrimental in the question of how to utilize science's powerful offspring – technology. Specialization creates an environment where the technology becomes an unchecked power shaping the greater social, political, cultural and ecological environments. Without greater societal checks and balances, technology and technologists focus simply on what the technology can do, not whether it should be done or how it might best be done influenced by the greater environment. It is unnatural selection chosen by the part, not how it fits the whole. Development of the technology becomes the end in itself. Outside their limited specialized knowledge, the scientist and technologist are no different from the rest of present society, lacking in any necessary larger whole view.

Restructuring the courts is not changing what they do, but one way of helping enfranchise a larger view in decision processes. Courts do and in ways will always legislate. In an era of great change, our ideas about law need to change, especially in regards to technology and its impact on our lives. Law defined by technology is not that of the ancient tradition of Moses coming down from the mountaintop with stone tablets inscribed by flame for eternity. It is quite the opposite. It is many times very ephemeral rules made amongst ourselves for how things should work. We need much more organic processes of law, facilitating technological evolution with a constant shaping by the concerns and experience of the whole society.

Democracy is a corrective for these problems. Opening these issues and reforming decision making processes to ever greater numbers in itself brings a more representative perspective. Obviously, this requires an evolving of democratic thinking, processes, and institutions, an acceptance of a Jeffersonian imperative each generation is rightfully endowed to revise and devise their own governance. An understanding, indeed an ethos, that the history of democracy has yet to be written.