God, Science, & Technology

There's a long running debate about god and science. A number of advocates over the last couple centuries claim science has buried god, however even a cursory look reveals this hardly to be the case. The first question one is forced to ask is whose god or which god, immediately conjuring all sorts of questions neither helpful or enlightening. Leaving those questions aside, it is without question knowledge gained through science has run roughshod over myths of all religions.

Reading Voltaire, he spends a great deal of time dismissing Judaeo-Christianity because science made obvious many biblical stories were incredulous. In many ways Voltaire had it backwards. Truly, the same thought that created religion was very much the thought that created science. Both stem from the human mind's struggle to understand the world and the universe we find ourselves existing. The thinking underlying all earthly religions is very much the process that gave us science. All religion sought to provide reason behind the seeming chaos of events surrounding, influencing, and impacting human life.

With religion, Homo sapiens developed the idea of causality, that every action is preceded by a previous action then followed by another. With this understanding, came the idea events were determined. The forces of nature, indeed our own actions were determined by greater forces. Today, it doesn't require delving too deeply into science to see these ideas, first created with religion, still lurking and very much alive, most vividly and importantly exemplified by the idea of determinism.

Causal relations are at the root of all science, where any event has been preceded by actions determining whatever follows. This determinism remains the foundation of all science. In many respects, scientific determinism became a new theology. There is a belief, certainly among many physicists and shared by many others, that from the first atom splitting, the universe was set on an inevitable course determined to the end of time. Eddy Keming Chen a “philosopher of physics” (Richard Feynman violently spins in his grave) at the University of California, San Diego, sums up deterministic belief in a piece in the eminent science journal Nature,

“Take Isaac Newton’s laws of motion. If someone knew the present positions and momenta of all particles, they could in theory use Newton’s laws to deduce all facts about the Universe, past and future. It’s only a lack of knowledge (or computational power) that prevents scientists from doing so.”

Newton was a rabidly fervent christian to the point he'd make a fundamentalist in the backwoods of Alabama, I suppose that's a bit of stereotype, probably better to say in the Halls of Congress, blush. His belief in an ancient deterministic god was essential to shaping his deterministic laws of nature. Four centuries later, Professor Chen brings Newton's determinism to the most bleeding edge of human technology development, compute technology. Underneath the development of much compute technology is a fundamentally deterministic faith, a belief only the lack of compute power and insufficient data are missing to predict an already determined future. Today, on a daily basis, technology creates ever greater myths and seemingly inevitable fantastical futures. God dead? Not by any means in the Tech Industry. Ironically, 20th century physics, specifically quantum mechanics, in part responsible for the very creation of the Tech Industry, challenged the idea of determinism, replacing the certainty of one action determining the next with probability.

Albert Einstein one of the founders of this physics, himself the great reshaper of Newtonian physics, remained until death a determined determinist. He once described his motivation, “What really interests me is whether God had any choice in the creation of the world.” He was determined to prove God had no choice.

It's fascinating what an important element determinist philosophy, not science, was in Einstein's ability to devise relativity. There's an excellent piece written by physics Professor Gerald Holton on the entanglement of Einstein's science and his religious thought. “He tried to dissociate himself from organized religious activities and associations, inventing his own form of religiousness, just as he was creating his own physics. ...the meaning of a life of brilliant scientific activity drew on the remnants of his fervent first feelings of youthful religiosity.”

As with all religion, Einstein's religiosity was most vigorous in its determinism even though his theories of relativity put a radical new spin on the very idea of perspective. Time and space became relative to an observer's position, the speed of light the only universal constant. Ten years later, with the creation of quantum mechanics, Einstein never accepted its indeterminate universe. Professor Chen's full article “Does quantum theory imply the entire Universe is preordained?,” offers a taste of the intellectual hoops physics has since jumped through in trying to keep determinism with attempts to unify Einstein's general relativity with quantum physics.

Life in the 21st Century is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

As queen of the sciences, physics' quantum indeterminacy was revolutionary, yet, over a half-century before, biology launched a similar revolution. An idea appeared with existential implications for humanity, Darwin's theory of natural selection. Copernicus removed the earth from the center of the universe, Darwin removed Homo sapiens from the earth's center. Evolution raised the idea of contingency. The great evolutionary paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould explains contingency as follows,

“The message of history is the theme of contingency. The world makes sense. It's enormously complex. It's full of random elements. What happens makes sense after it happens, if the density of historical information be great enough. It often isn't. That's just the impoverished nature of the record but that's a problem in all historical reconstruction.”

Gould continues explaining the important difference between contingency and determinism, especially in regards to many today advocating a simple need for more powerful compute technology and enough data:

“If the density of evidence be great enough one can explain what happens. It's not an accident, what happened makes sense, but it's not subsumable and predictable under the laws of nature. It's a complex, unrepeatable, unpredictable set of historical contingencies in what happens at the end is so critically dependent on each of the thousands of antecedent steps each happening as they did. No one of which had to happen that way.”

“If you could in fact do the great thought experiment, which unfortunately we can't, of erasing life's tape, running it all back and letting it go again would you get anything on the surface of this planet like what we have? Under the biases (determinism) you would get something very close to it, all this is very predictable. Under contingency, you'd never get anything even close to what we see, but you wouldn't get chaos, you'd get a totally different result. It would be equally explainable. The only problem that the chance of it including any conscious creature desiring to explain it would be very small indeed.”

This is a wonderful, succinct exposition of a terribly important concept. It is antithetical to the popular analogy at the beginning of the Scientific Revolution of the universe as a clock. Set in motion, the clock and all its gears will predictably and infinitely go forward – all order deterministically prescribed. Gould emphasizes contingency is not anti-causality. Looking backwards, every given action results from a specific previous action. However, looking forward, you cannot determine precisely which action will happen, unlike a wound clock, the future cannot be precisely or even at times depending how far forward you go generally determined.

Gould continues about determinism’s still dominant mind hold,

“We're trained in this hierarchical status ordering of the sciences to think subsumption under nature's laws as better, as more elegant, as a deeper kind of explanation and of historical contingency as a somehow less preferable and messier. It's not true. Contingency is almost never taught.

There are realms of historical sciences, cosmology, paleontology, geology, and large parts of evolutionary biology that are sort of downgraded in this status order. We don't learn very much about contingency in science. If you want to study contingency, it's a theme much better exploited by humanists, by film makers, by authors, by novelists than by scientists.”

Contingency is part of technology's development, yet this is very little understood and dangerously ignored by technologists, who like to proselytize technological determinism in direct opposition to atomic bomb developer J. Robert Oppenheimer. In a 1958 speech, Oppenheimer talked of the accidental nature of plenty of tech development and of science itself:

“It is a very accidental thing, and again I would say it must be historians and not by logicians as to what effect, if any, developments in science have on human life. I mean that not primarily in terms of the mechanical differences, although here to it seems to me there's been some mighty odd accidents. Things could have been done with scientific knowledge which lay fallow for a long time because they didn't have any great sex appeal for the economy or the industry of the time and things get done in a great hurry like making an atomic bomb, almost before you knew how, because they do have a great sex appeal. A good deal could be written about the randomness and lack of logic in the relation between what we learn how to do and what we in fact do do.”

Oppenheimer and Gould agree this process isn't best or even at all understood by logicians and engineers, but only through history. “What we learn how to do and what in fact we do do” are both contingent.

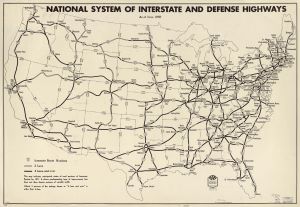

A simple example of contingency from the recent past combines science, technology, politics, and the development of the American interstate highway system in 1956 with the passage of the “National System of Interstate and Defense Highways Act.” Passage of the law was contingent on the Cold War begun a decade before. The Cold War was contingent on World War II, which was contingent on Adolph Hitler. Hitler's rise to power was contingent on the Treaty of Versailles, contingent on World War I. None of these events were automatically determined, all could have been avoided. After all, the magnificent thinker John Maynard Keynes warned in his prescient Economic Consequences of the Peace against the Versailles Treaty – no Versailles, no Hitler. Similarly, over the last half-century, the present shape of every major city and the decline of many small towns across America were both contingent on the building of the interstate highway system.

With historical thinking and political affairs, Tolstoy expressed the importance of contingency in the second epilogue of War and Peace (1867). He writes,

“For an order to be certainly executed, it is necessary that a man should order what can be executed. But to know what can and what cannot be executed is impossible, not only in the case of Napoleon's invasion of Russia in which millions participated, but even in the simplest event, for in either case millions of obstacles may arise to prevent its execution. Every order executed is always one of an immense number unexecuted. All the impossible orders inconsistent with the course of events remain unexecuted. Only the possible ones get linked up with a consecutive series of commands corresponding to a series of events, and are executed.”

Tolstoy concludes, “However accessible may be the chain of causation of any action, we shall never know the whole chain since it is endless, and so again we never reach absolute inevitability.”

Tolstoy argued against the then popular, deterministic, great man school of history. He suggested history was immensely more complex than what most perceive today, such that a 21st century American perceives history at all. “The lesson of contingency is the things that seem utterly unimportant for the moment can be those tiny little changes that send history cascading down different pathways.” (Gould)

From a humanist view, a biological perspective, and with the equations of 20th century physics serious obstacles to a strictly deterministic view of life have been raised, fairly conclusive objections. Nonetheless, today, determinism remains strongly advocated, peculiarly and particularly as an exclusive force in the development of technology. It is found in the refrain, “you can't stop it,” or more recent advocacy of speeding tech development, dubbed accelerationism, as some sort of panacea to solving the great problems caused by the past's indiscriminate and still unmitigated tech development. Underlying both notions lies the idea tech development is predestined to go somewhere, that indiscriminate, continuous technology development is in itself, just as the gods previously, determinant.

With the addition of information, questions regarding determinism versus contingency gain greater complexity, seemingly answered overwhelmingly in favor of contingency. The great mathematician and scientist Norbert Wiener stated, “Information is neither matter or energy.” Using feedback, systems incorporate information that manipulates both energy and matter. Feedback is the most important, least understood, scientific concept of the last two centuries.

South African physicist George Ellis states, “The point of a feedback control system is to make the initial state irrelevant as opposed to classic physics in which the initial state determines outcome.” A decade ago, in a wonderful talk given in Krakow, Ellis explains new order created through feedback. He talks of top-down constrained order as opposed to bottom-up, which until recently in the physics' world would pretty much be heresy. As Ellis explains the top establishes “goals” which in turn constrain the bottom. The “top” in this case is order created through feedback. The bottom then the initial state reshaped and constrained by information fed back. “Details of the microstructure control the macrostructure and the macrostructure returns down controlling the microstructure.”

Understanding such systems requires the concept of emergence, simplistically defined as the whole being something greater than the sum of all its parts. A great example of this are the 50 – 100 trillion cells that comprise the human body. Each of these cells can be perceived individually but only truly understood in context of their combinations and interactions. Each cell is defined with the organization of individual organs, innumerable processes, and finally the emergence of the human individual.

Human existence, all life, relies on homeostasis, the equilibrium of complexity gained through feedback. Body temperature, heartbeat, blood pressure are all comprised of countless cells “each governed by implicit goals, embodied in the physical structure of the the body.” Ellis adds the seminal physiologist Arthur Guyton, whose textbook is still standard issue in medical schools, conceived the human body composed of thousands of such systems.

All biological organisms are information dependent systems. “They all have built in through the adaptive process of evolution and embody images of the environment.” (Ellis) This is such a wonderful statement, not well understood by most professing evolution. It is a simple, eminently profound understanding that no organism can be understood outside the context of the greater environment in which it was created. Indeed, that greater environment is incorporated into the organism.

With technology development, adopting understandings of contingency and feedback allow an ability to choose and shape technology, an ability at this point that should be perceived necessity for no other reason than allowing us to survive the technology we've already adopted. Without a better understanding of information and feedback, technology development will become even more exclusively determined by a handful of people and increasingly the technology itself. The idea of tech development determined simply by tech development needs to be vigorously opposed. It is the ultimate ignorance of understanding how we've come to be who we are.

In Nature and the Greeks, quantum physicist Erwin Schrodinger sought to reveal “what I deem to be the peculiar fundamental features of the present-day scientific world-picture. To prove that these features are historically produced by tracing them back to the earliest stage of Western philosophic thought.” It is not simply science that has been historically produced, but politics — the social, cultural, and government institutions surrounding us. Each contain fundamental ideas of determinism as harmful to shaping the future of humanity as tech determinism.

Reforming all these processes needs understanding information and feedback, and a resulting reorganization of institutions and processes. Information and feedback have not just essentially shaped human history, but the history of life. Whatever technology we create, that history will always very much be part of life, ours and all that created us.