Marathon

History is sculpted by innumerable small events and the acts of multitudes of people. At certain points, certain times, the whole of history's indomitable force is channeled in a certain direction, a direction few previously predicted. At such times and places, a single event, the very acts of a specific individual can fundamentally alter the flow of history's currents.

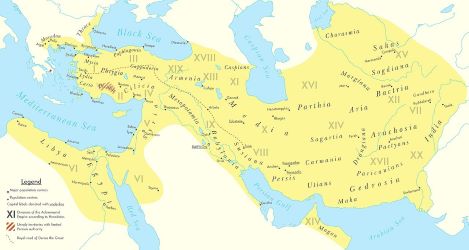

One such event was the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC, where the small, newly democratically enfranchised city-state of Athens defeated the vast Persian empire. If the Athenians had not prevailed in this most classic underdog victory, the Greco-Roman foundation of Western civilization would have never been laid. It is not hyperbole to say there would have been no Aeschylus, Sophocles, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, or Alexander. Darius, the Persian “King of Kings,” may not have stopped at Greece, infant Rome would probably have been smothered in its cradle.

Marathon lies approximately 25 miles from Athens. It's known widely today only for its namesake foot-race, commemorating the unknown soldier's run to bring Athens news of their victory. On this ancient battlefield, 10,000 Athenians and their 1000 Plataean allies defeated 25,000 Persian troops. Contemporary Greek inscriptions at the site describe the Persians as, “Heir to a tradition of imperialism, of the Assyrians and Babylonians, going back thousands of years. In the reign of Darius it had reached the peak of its power, surpassing all precedent in territorial size and organization.”

Of the Greeks they write, “On the other side, young Greece, fragmented into cities fighting against each other, was anything but ready for a fight of this magnitude.” This fragmentation kept away the Spartans with the biggest Greek army, leaving only the Athenians and a small contingent of Plataeans. This suited Darius the Great fine. The Persian King of Kings had it in for Athens after they had recently come to the aid of the Ionian Greeks in their revolt against Persian rule.

The battle was short. The tight Athenian phalanx routed the loosely organized Persian army. The Ancient Greek historian Herodotus writes a 194 Athenians were killed while Persia lost 6,400. Occurring less than two-decades after Cleishtenes established democratic rule, Athens' young democracy gained immortal renown.

Today, the Athenian Tumulus still rises in the middle of the ancient battlefield. The mound contains the interred remains of the fallen Athenians, an exceptional act. Fifty years later, Pericles would call attention to this exception in his famous “Funeral Oratory,”

“The dead are laid in the public sepulcher in the beautiful suburb of the city (Athens), in which those who fall in war are always buried; with the exception of those slain at Marathon, who for their singular and extraordinary valor were interred on the spot where they fell.”

It is truly an unequaled site of historical substance.

As monumental as Marathon was, it was the first of two historically determinative events. The second occurred ten years later with the great naval battle of Salamis, led by one of the great democratic historical figures of all times, Themistocles, who had been a young commander at Marathon. The Roman historian Plutarch claims Themistocles was alone amongst the Athenians to realize the Persians had been beat but not defeated. He argued to his fellow-citizens the Athenian army was insufficient to repel a second invasion and advocated building a navy to intersect the greater Persian force at sea. He convinced the Athenians to forgo payment they all were due to receive from a newly discovered vein of silver at the Laureium mine and instead use the funds to build the ships.

“I cannot fiddle but I can make a great state from a little city.”

Themistocles' story offers incredible lessons, none more so than an essential fact it reveals about the nature of money. If the Athenians had not diverted the silver, they would not have been able to build the ships. It's one of the first historical examples of the exogenous power of most money used across history. The labor, wood and all resources were available to the Greeks without any silver. The labor to extract the silver entirely irrelevant to the building of the ships, yet, it was only by passing the silver was the navy built. It could have just as well been another, in the words of the economist John Maynard Keynes, “fetish,” such as copper, shells, or avocados, used to accomplish the same thing. It's a fundamental fact for any consideration of what exactly is money. Funnily enough, an issue neither the Greeks or few since ever dealt with.

Maybe most antithetical to the present era, Themistocles convinced the polity to forgo immediate gain for what must have seemed to most Athenians a rather fantastical and by no means guaranteed enterprise for the future common welfare. What could be a more abhorrent idea to the present culture of individualist instantaneous gratification, valuing not a day in the future or remembering a minute into the past?

Finally, Themistocles building of the navy provides an excellent historical lesson in the politics of technology. Athenians considered themselves a land based culture. A founding legend concerned the goddess Athena defeating god of the sea Poseidon for control of Athens. The contest was memorialized on the west pediment of the Parthenon, Athena's great temple. Turning to the sea by building a navy was fundamentally contradictory to Athens' character. The philosopher Plato wrote a century later, "Themistocles robbed his fellow-citizens of spear and shield, and degraded the people of Athens to the rowing-pad and the oar." (Laws)

To the reliably anti-democratic Plato's chagrin, the establishment of the navy helped secure democratic order in Athens. It’s an astoundingly hypocritical lambaste against the very act that made Plato himself possible. His always wiser student Aristotle accurately states,

“The victory of Salamis, which was gained by the common people who served in the fleet, and won for the Athenians the empire due to command of the sea, strengthened the democracy.”*

Life in the 21st Century is a reader-supported publication. Please become a paid subscriber.

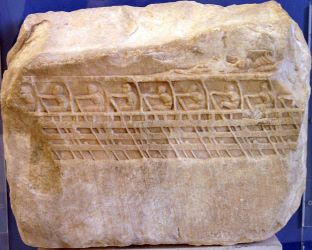

The Athenian navy was comprised of triremes, the origins of which are unclear. Triremes had three levels of rowers seated on each side of the ship, totaling 170 oars according to Thucydides. Crews numbered 200 in total. Adding approximately two hundred ships over the course of a decade altered not simply Athens’ military capabilities, but helped entrench the new system of democracy by creating a strong block of four-thousand “common citizens” in a city containing at most 40,000 citizens. A half-century later, at the beginning of the Peloponnesian War, Pericles claimed 300 ships had been built, meaning an even larger block of six-thousand citizens.

In Politics, Aristotle describes the new democratic political order,

“For both in the common people and in the notables various classes are included; of the common people, one class are husbandmen, another artisans; another traders, who are employed in buying and selling; another are the seafaring class, whether engaged in war or in trade, as ferrymen or as fishermen. (In many places any one of these classes forms quite a large population; for example, fishermen at Tarentum and Byzantium, crews of triremes at Athens.)” *

Four centuries later, Plutarch commented on Themistocles' democratic innovation,

“And so it was that he increased the privileges of the common people as against the nobles, and filled them with boldness, since the controlling power came now into the hands of skippers and boatswains and pilots.”

What an example of the politics of technology! The building of the trireme navy entrenched and strengthened Athenian democracy. This defining technological political evolution was remarked on by ancient commentators, yet in our present era, where every aspect of life is defined by technology, the resulting politics are not simply ignored but dismissed.

The Battle of Salamis took place in 480 BC, a decade after Marathon. Today, the land battle of Thermopylae immediately preceding Salamis is better known, mostly through the goofy movie, “300.” The movie does tell the very real story of the small Spartan force led by Leonidas, who by being massacred, slowed the advance of Persian land forces. Such senseless slaughters sanctify many military legends, preaching death as the highest honor.

The forces of the now new Persian king Xerxes, Darius' son, moved down from Thermopylae, sacking and burning Athens. Maybe Themistocles greatest act of political persuasion was before the sea battle convincing the Athenians to abandon Athens and move to another city. This might be the first recorded, but by no means last strategic abandonment of a city. One is led to think the classically educated Tsar Alexander knew the story as his army lured the little French corporal deeper into Russia, setting Moscow aflame at the very moment Bonaparte perceived French triumph.

With Athens abandoned, the naval battle took place directly off the coast in the Straits of Salamis. Plutarch describes,

“Now the first man to capture an enemy's ship was Lycomedes, an Athenian captain, who cut off its figure-head and dedicated it to Apollo the Laurel-bearer at Phlya. Then the rest, put on an equality in numbers with their foes, because the Barbarians had to attack them by detachments in the narrow strait and so ran foul of one another, routed them, though they resisted till the evening drew on, and thus 'bore away,' as Simonides says, 'that fair and notorious victory, than which no more brilliant exploit was ever performed upon the sea, either by Hellenes or Barbarians, through the manly valor and common ardor of all who fought their ships, but through the clever judgment of Themistocles.'"

Considered one of the great literary figures of Ancient Athens, whose works are lost to our age but not Plutarch's, Simonides accurately credits Themistocles, though his story doesn't end here. A few years later, Themistocles is ostracized from Athens, paradoxically making his way to a Greek city in present Turkey under the domain of the Persians. There, Xerxes allows him to live rest of his life in comfort.

Ostracism, forced exile, was a tool sparingly but effectively used by democratic Athens to control power-lust of even its most distinguished citizens. Plutarch explains Themistocles and the practice of ostracism,

“Well then, they visited him with ostracism, curtailing his dignity and preeminence, as they were wont to do in the case of all whom they thought to have oppressive power, and to be incommensurate with true democratic equality. For ostracism was not a penalty, but a way of pacifying and alleviating that jealousy which delights to humble the eminent, breathing out its malice into this disfranchisement.”

Themistocles couldn't really complain, nor did he. After all, he himself led the charge a decade before to ostracize Aristides for being too Sparta friendly. Aristides returned from exile right before Salamis and provided essential support in gaining Spartan approval for Themistocles' battle plans – such is the complexity and maturity of the healthiest of democratic politics.

Ostracism was maybe the greatest tool of democratic Athens against oligarchy and tyranny. It grew from the very greatest egalitarian ethos of democracy – ability and power lay not exclusively or predominately in any one individual or group of individuals, but in the value, thinking and actions of the entirety of the polity. In present America, no democratic attribute is more degenerately degraded than this. Instead, individuals' wealth accumulation, media celebrity, and the perpetual holding of elected office to the point they leave only when laid out on a slab, are all held in highest esteem.

Today, Marathon is the lost and unappreciated story of how literally the West was won. Writing four-hundred years later, the Roman historian Livy states in the middle of the Roman republic's Conflict of the Orders, three decades after Marathon, Rome sent a delegation to Athens to study their laws and institutions. Upon their return, the Romans established the plebeian assembly and soon after enfranchised the plebes' law making capabilities. As democracy is such an anomaly across recorded human history, it's by no means controversial to say without Marathon. it would have never existed at all, nor much of most anything else we consider Western.

* Thomas Mitchells' footnotes in his outstanding history, Athens: A History of the World's First Democracy (2015) pointed me directly to a couple of these ancient sources.