Mycenae and The Eumenides

Mycenae is a historic and legendary city of Greece. Inhabited since 5000 BC, its glory years spanned 1600 to 1100 BC. This late Bronze Age Mycenaean civilization stretched across the Greek mainland. It's influence on the Greek civilization that followed, between 800 and 400 BC, mostly a matter of conjecture. The great collapse of the Bronze Age civilizations of the Eastern Mediterranean, including Mycenae, occurred 300 years before the origins of what we know as Classical Greece.

Mycenae is spectacularly perched on a hill above a fertile plain stretching across to the even more ancient city of Argos, just beyond Argos the “wine-dark” Aegean is visible. On the top of the hill sits the ruins of the small walled acropolis that served as a political center with palace, temples, and fortress.

One thing we do know of these Bronze Age cultures, particularly Mycenaean and its immediate influential predecessor the Minoans centered on the island of Crete, politically, they were highly centralized. Archaeologists define them as “palace cultures.” The most important thing both civilizations bequeathed to Classical Greek's decentralized city-states was their collapse.

However, Mycenae holds an immensely important place in Ancient Greek mythology and culture. From Mycenae hails the great King Agamemnon. He united the Greeks to retrieve his brother's wife the heavenly beauty Helen, who had sailed away with Paris and the Trojans. “And as for Troy, there she brought a dowry of destruction,” Aeschylus ruefully notes of Helen's legacy. Of course this is the great story of the Iliad, attributed to Homer sometime from the 8th century BC, three centuries after the collapse of Mycenae.

An interesting thing about Greek mythology established by Homer is it continually evolves for another thousand years. For example, today, maybe the most popularly known element of Troy is the great wooden Trojan Horse, which never appeared in the Iliad and mentioned in only one line of the Odyssey. The story known today was largely fleshed out by the Roman, Virgil, eight centuries after Homer.

No era was more profound in shaping Homer’s Greek mythology than that of the great tragedy and comedy play writes of classical Athens, three or four centuries later. In The Oresteia, the great tragedian Aeschylus uses Homer’s story to directly tie legendary Mycenae to the founding of Athens' democratic courts and jury system. The Oresteia trilogy is named after their protagonist Orestes, Agamemnon's son. The main plot line first appeared in Homer's Odyssey.

Agamemnon is the first play. After spending ten years away fighting at Troy, the king returns to Mycenae accompanied by his Trojan captive and mistress, the haunted Cassandra, whose horrifying premonitions of the future of Troy and then her Greek conqueror prove all too true.

Agamemnon's wife, Clytemnestra, still has it against him that ten years before, in order to gain favorable winds for the Greek fleet to embark against Troy, at the behest of the goddess Artemis, he sacrificed their daughter Iphigenia. Phew, those Greeks! Incessantly harried by the immortal gods, though always their final fate directed by their own mortal hands. No sooner is he through the door then Clytmnestra and her lover Aegisthus murder Agamemnon and Cassandra.

Life in the 21st Century is a reader-supported publication. Consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

In the second play, The Libation Bearers, Orestes, who was gone while his father was murdered, returns. In vengeance at the behest of the god Apollo, Orestes kills his mother and Aegisthus. Of course killing a parent is one of the ultimate sins of not just Greek but all human culture. For his crime, Orestes is bedeviled by the Furies, three goddesses representing vengeance and a certain crude justice. Orestes is driven mad and into the wilderness.

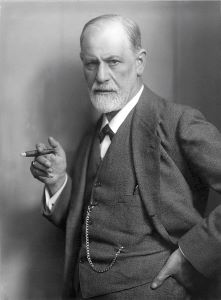

Here, we might ask ourselves, what would modern 20th century culture have looked like if instead of obscenely misinterpreting the actions of Oedipus, the quack Viennese doctor had chosen Orestes? No, we didn't want to bed our mothers, but kill them. Of course Oedipus had no idea the woman was his mother, but the disturbed Austrian sought to begat all sorts of secular incantations seeking to calm the modern Furies. Looking culturally at the 20th century, it would be hard to attribute anything more socially destructive or harmful than this misinterpretation of the Greeks creating a new and highly profitable school of myths, resulting in a culture of narcissistic self-absorption. One thing for certain, don't blame the Greeks.

In the third play, The Eumenides, it is clear we remain both beneficially and essentially indebted to the Greeks. From the wilderness, Orestes turns up at Delphi to appeal to the god Apollo, who had directed Orestes' revenge killing. Apollo distressed at the Furies torment of Orestes turns to the wisdom of the goddess Athena. She decides to hold a trail on the “Hill of Ares”, which in Aeschylus' time was used for trials.

Athena states,

“Men of Attica, hear now my decree: You will be pronouncing judgement upon the first trial ever involving bloodshed. This court of judges will for ever rule in the land of Aegeus (Athens).”

(It should be noted, judges would today more resemble jurors. Trails were all conducted and decided by an assembly of a segment or of all the citizenry.)

At the time Aeschylus wrote, democracy was brand new. He founds the jury trial with the gods. Aeschylus attributes to Athena the removal of the tradition of family and tribal blood revenge. In its place she creates a nonviolent civic process comprised of the larger Athenian polis.

Athena declares,

“I now establish this court. Neither profit nor lust should violate it and it should remain an august guardian of the land, vigilantly defending those asleep, and quick to avenge. These then are my words uttered for the good of my citizens for all future. Now let every man stand, pick up his ballot, think of his oath and judge accordingly.”

It is not simply the establishing of a court, but an assembly of the citizenry deciding by vote. Apollo then counsels the jurors before this first ever casting of votes,

“Friends, be sure to count the votes accurately. Be careful you don’t make any mistakes because mistakes in judgment are followed by great disaster. One less vote destroys a house, another, saves it.

The vote is tied, thus Orestes acquitted in this new political process, the first decision civilly addressing the most heinous crime of matricide. The Oresteia’s celebration and honoring of democratic politics was first performed in front of the entire citizenry of Athens, during their biggest festival, the Dionysia. The play reinforces justice as the foundation of civil order. For the Greeks, justice was the essential political principle.

More ancient than Athena, the Furies are not happy. They represent the old family and tribal justice of vengeance. The eye for eye unending cycle of violence that disallows larger civil harmony. The Furies cry,

“O gods! Gods of the younger generation! You’ve dishonored the old laws. You’ve snatched them from my own hands! And I, now with no honor, wretched and with anger heavily weighing on me shall spew upon this land the vindictive poison, the poison in my heart.”

But Athena seeks to calm the Furies assuring them justice has indeed been accomplished. She pleads to the Furies the merits of this new process,

“Listen to me! No injustice has been done and none suffered by you. I understand Justice and promise you that you shall have temples and lawful crypts in the land, to sit on bright thrones and altars and to be honored by these citizens.”

Thus Aeschylus ends his play with a warning to honor justice and the democratic systems procuring it. Without them, the Furies will rule. In Ancient Athens, the mythical legends of Mycenae were sculpted into a very hard political reality.

Today, directly descended contemporary versions of democracy stretch across the planet. Standing at the top of the Hill of Ares, Athena needn't look hard to see her systems neither honored or producing much justice, assurances to calm the Furies of little avail.

You can share Life in the 21st Century via: Reddit, Twitter, Facebook