Natural History

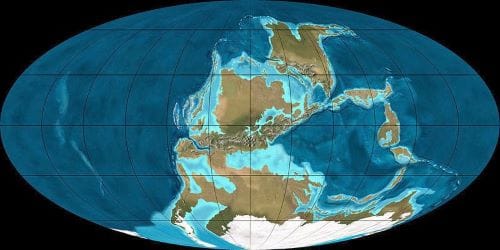

Thomas Halliday’s Otherlands is a valuable history book. It's a history of earth stretching back 550 million years composed of chapters of a variety of geologic periods and the life forms existing in each time. It's a book that would be more invaluable as series of images. To his credit, he includes maps of each era, unfortunately the value of including maps is something lost to the book business these days.

History provides context for how and where we've come to be. Much of the time, it is the only context. Too often in the past, knowledge of history was used as a straight jacket in shaping human affairs, instead it should be approached as a vital key to freedom. In regards to freedom, after two centuries of industrial technology, historical perspective is more important today than at anytime in the past. The implementation of any technology always destroys part of the past, industrial technology has steam-rolled the past, constructing a present wrongly considered to be severed from all historical roots. Nothing could be further from the truth. Knowledge of the past allows pre-industrial perspectives, perspectives that can help create more varied and vibrant futures.

In a great chapter on the 300 million year ago Carboniferous Period, Halliday directly ties the Industrial Era of the last two centuries to earth's deep past. During the Carboniferous, over the course of tens of millions of year, the earth's vast coal beds were created. At this time, much of earth's land masses were hotter and wetter. “The equatorial sun of Carboniferous Illinois is blinding and white.” Plant life exploded. Halliday describes the tree-like Lepidodendron,

“Standing close-knit in the peaty mire is a large patch of trees, each no more than a couple meters from its nearest neighbors and relatively uniform 10 meters tall. Their trunks are crocodile-green, and textured with diamonds overlapping like scales. …from halfway up each tree to its top, each scale lends support to a single long, thin leaf, a dark brushy bristle, which intermeshes with its closest neighbor.… The light that shines through the sparse canopy can still be brought to use; in the scale tree, Lepidodendron, every part of its diamond-patterned side remains photosynthetic, the whole of the bark able to turn air and sunshine into new plant material.”

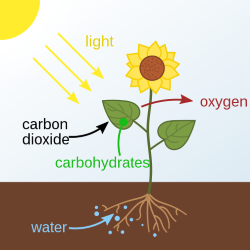

It is difficult to imagine the energy stored in coal, oil, and natural gas is all derived from ancient sunlight. Photosynthesis, the great energy process of life, takes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, water from the ground, and light from the sun creating chemical energy for the plant. Oxygen is the byproduct released. Carbon from the atmosphere becomes the plant's main building material. Few understand plants are overwhelmingly creations of the atmosphere, roots providing only stability, water, and a few minerals from the soil. In burning plants or their fossil fuel remains, carbon is released back into the atmosphere, the fire itself a release of the stored sunlight.

Halliday writes of Carboniferous' abundance of carbon, water, and sun:

“With the development of the first tall, tree-like plants – Calamites, scale trees, and the conifer-like codaites – all of these ingredients are at their greatest abundance during the Carboniferous. Never before has so much material been concentrated in plants.”

Over tens of millions of years, the remnants of this great mass of plants become the coal beds used to fire industrialization three-hundred million years later. The processes that defined human life over the last two and half-centuries resulted only from processes occurring three-hundred million years ago. Halliday writes,

“The irony is that, because of the coal laid down throughout the Central Pangaean Mountains, these places – Illinois and Kentucky, Wales and the West Midlands in Britain, Westphalia in Germany will play a critical role in the earliest rapid industrialization of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries – the driving force behind the re-release of carbon stored beneath the earth for the last 309 million years. Some 90 percent of all coal on the earth today was deposited during the Carboniferous. It is the sheer abundance of coal, where it was laid down that made it such a cheap, high-energy fuel choice for industrialization, powering steam engines and becoming part of high-quality steel. The legacy of the scale trees lives on.”

Little of the history of industrialization properly regards the development of the first great industrial powers was contingent on a process three-hundred million years ago. Nor, that it was a simple matter of happenstance that industrial US, Britain, and Germany advantageously sat atop these coal beds. This fundamental element of industrialization, its deep history, has mostly been ignored. It has been brought to attention only with the larger environmental feedback caused from industrialization's mass burning of fossil fuels.

Life in the 21st Century is a reader-supported publication. Please become a paid subscriber.

In burning coal, oil, and natural gas, the energy entrapped, ancient sun energy, is released for work, whether for pushing four thousand pound cars, forging steel, spinning rotors to generate electricity, or radically altering existing ecological systems. Plants largely products of the atmosphere, upon burning, re-release carbon into the atmosphere, changing the atmosphere's chemical content and altering whatever processes are dependent on the atmosphere, for example climate.

The riot of plant life that occurred in the Carboniferous was contingent on the carbon in the atmosphere – “a number ten times higher than the total amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere today.” Yet, “compared with the beginning of the Devonian 110 million years before the Carboniferous, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere had fallen.” After tens of millions of years of plant proliferation, the carbon in the atmosphere had drastically decreased to the point Hadley writes,

“Innovators like the scale trees are radically changing the composition of the atmosphere. The Earth is spiraling towards climate change that will lead to a cooling almost to the point of a global ice age, an increase in seasonality and in aridity, and, ultimately, the wholesale destruction of the very ecosystem that keeps the scale trees alive. This will be their extinction, as the sodden coal swamps of the Carboniferous give way to the drought of the Permian. By removing carbon in such quantities from the atmosphere, they set the stage on which evolution would play out for the next third of a billion years.”

I love he uses “innovators,” a term in our era of almost godlike veneration. Innovation without context is to say the least problematic. Innovation ignoring feedback is the definition of stupidity. Context can be provided in many different forms, cultural, political, historical, environmental (which in many respects, for example all evolution, is a type of history), and technological. Industrial innovation has largely been valued with limited context and increasingly context is provided exclusively by existing technologies. Industrial technologies have so reshaped human society and the larger environment that certain technologies are perceived as necessity, future innovation constricted by their very existence, certainly no greater example is the United States and the automobile.

Just as importantly, we have ignored the feedback returned from technology's implementation, whether this feedback is social or environmental. We have ignored the fact technology does not in anyway remove us from the greater established systems of this small planet. That tweaking one aspect of any system, always results in a reaction creating a new system. Our very definition of intelligence is the ability of a system to incorporate feedback from actions already taken to influence any future actions, with technological development we not simply fail, but flaunt the very notion.

History provides context for the present. In tech defined culture, history is buried, deemed irrelevant, yesterday is forgotten instantaneously. Yet, the whole of industrialization and modernity were defined by a literal digging up of the past. A past now resurrected into the atmosphere. This was done out of ignorance, in the name of innovation. An incapacity to incorporate the feedback of these and many other of our industrial technological actions reveals not a lack of information, but a systemic, or maybe better, a species lack of intelligence. The ability to create species wide intelligence is politics.