Oracles of Delphi and Chicago

Delphi was the most sacred city of Ancient Greece. The Greeks considered Delphi the center of the earth. It is spectacularly situated half-way up a mountain, looking down a narrow valley widening into the Gulf of Corinth. Directly behind, rising a thousand feet, tower steep granite cliffs colored red, gray, and gold. Delphi was the sanctuary of Apollo, the sun god of music, harmony, and light. In Apollo’s temple resided the Pythian oracle visited from across Greece and lands afar by supplicants looking for guidance and prophecy of the future.

Held in equal importance across the whole of Greek civilization, Apollo was the “national” god of Greece. Delphi his most hallowed temple. Every four years Delphi held a Greece-wide musical contest and athletic games known as the Pythian Games, second only to the Olympics in stature. Over the years, Delphi developed an almost Disney-like environment. City treasuries, monuments, and statues rose from across Greece, and in later centuries from Rome, all dedicated to Apollo in gratitude for victories in battle and athletic contests, along with a variety of political and personal successes.

The Delphi founding myth stated his temple stood where the child Apollo slay Python, the great serpent protector of Gaia, the goddess of earth and mother of all life. Pythia (python) became the title of the priestess oracle. Believed to directly emanate from Apollo, the meaning of the oracle’s ambiguous prognostications were very much dependent on the interpretation of the inquiring petitioner.

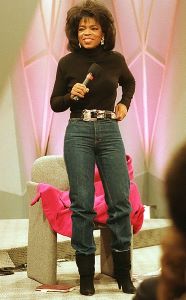

In many ways, the oracle might best be considered an ancient Oprah, espousing guidance for city, king, warrior, or person. The differences between the ancient Pythia and the modern Oprah say more about the two ages than the respective oracles.

The Delphic oracle appeared sometime in the 8th century BC and operated until the 4th century AD. For a thousand years, pretty much everyone who was anyone made their way to Delphi. Greek and Roman literature claim hundreds of prophecies credited to the Pythian Oracle, no doubt many apocryphal. Lycurgus, Sparta's great law giver and Athens' Solon both credited inspiration for their cities' constitutions from Delphi. In the 6th century BC, the Lydian King Croesus' prophecy rates the most infamously ambiguous. Asked if he should make war on the Persians, the oracle foretold, “A great empire would be destroyed.” Unfortunately for poor Croesus, it was his empire destroyed, not the Persian's.

One of the greatest and most amusing Delphic oracles is provided by Plutarch. Four centuries after the fact, Plutarch writes in his Lives about the Macedonian Alexander’s visit to Apollo's temple on his way to conquer the world. Plutarch writes,

“Then he went to Delphi, to consult Apollo concerning the success of the war he had undertaken, and happening to come on one of the forbidden days, when it was esteemed improper to give any answer from the oracle, he sent messengers to desire the priestess to do her office; and when she refused, on the plea of a law to the contrary, he went up himself, and began to draw her by force into the temple, until tired and overcome with his importunity, "My son," said she, "thou art invincible." Alexander taking hold of what she spoke, declared he had received such an answer as he wished for, and that it was needless to consult the god any further.”

Such is the personality needed for world conquering!

Life in the 21st Century is a reader-supported publication. Consider becoming a paid subscriber.

A Greek, Plutarch was for a time a priest at Delphi, however this was at the end of the first-century AD. At this point, the Romans had been in control of Delphi for over two-centuries. It had seen better days. The former Treasury of Athens was now a pawnshop. Once the Romans took over in the second-century BC, Delphi began to lose its political significance with power moved to Rome. For the Greeks, the oracle's significance had been overwhelmingly political, for Rome it was largely a tourist destination, entertainment, which brings us to Oprah.

Like the Pythia, Oprah is a woman held in god-like esteem. People look to her for guidance and prophecy. However, the differences between the two, best contrast the eras. Delphi is situated in a sensationally beautiful natural setting. The Temple of Pythian Apollo, other buildings, and monuments of great variety combined to make Delphi one of the most spectacular physical sites of the ancient world.

Oprah's temple couldn't have been more different. Harpo Studios opened in a decrepit and largely abandoned warehouse district just west of Chicago's downtown. Certainly, nothing could be more dramatically in opposition than a 5th century BC walk up Delphi's Sacred Way to engage the Pythia in Apollo's Temple, than a 1990’s walk down Chicago's Washington Street to “The Oprah Winfrey Show” in Harpo Studios.

This perfectly illustrates the greatest difference of the eras, the aesthetic of beautifully designed, touchable physical space replaced by the seeming ethereal magic of electric technology. Oprah had no need for an elaborately designed city elaborately or building, only a large room, with a hundred seats, lights, a small decorated stage, cameras, and a satellite dish to broadcast daily into the homes of tens of millions of Americans.

No need for pilgrimage to Chicago and Harpo Studios, just turn on the television and there, in your living room, appeared the Oracle of Chicago. Unlike the Pythia, Oprah was decidedly apolitical. As a medium, television had developed decidedly unpolitical. At first controlled by three and then a handful of massive corporations, television was overwhelmingly an entertainment medium, its primary purpose to sell consumer goods produced by leviathan corporations. Oprah's supplicants needn't bring offerings to Chicago, they only needed to purchase goods from her advertisers. Oprah claimed greater wealth than all Delphi could ever dream.

Oprah preached the era’s narcissistic individualism. The modern ethos of individuality devoid of greater social context, context the Greeks well understood was provided by a healthy politics – an ancient understanding of the inherent and valuable communal identity of Homo sapiens. As Aristotle put it, “Humankind is by nature a political animal.”

Instead, and she certainly was by no means alone but vastly influential, Oprah guided her largely female adherents to fill their experiential social void, created by modernity's destruction of formerly established community, by looking within themselves, not outward with active participation in recreating a greater society. She populated her shows with self-help gurus, whacked psychology, new age mysticism, and celebrity worship – modernity's gods.

Oprah touched little on politics, though many sought her blessing, or tangentially, such as when Tipper Gore talked about her fight with depression. Hey Tipper! Here's a clue. You're married to Al. Oprah's few direct political engagements proved at very best problematic. Then in 2004, Oprah best defined the modern oracle by giving every member of her audience a car. What better prescription to make an American whole? It is not a coincidence our popular Tech oracles are still automobile prophets.

The greatest difference between ancient oracles and today's are the Greeks limited practice to a few, with political prognostications largely their bread and butter. Today, oracles are a widespread profession, few, besides pollsters, tied to politics, though it can certainly be argued the ambiguous drivel offered by professional pollsters has little political value. Most contemporary oracle guidance is tied to gaining wealth, such as economists and market analysts, who are more about predicting the future than offering any valuable perceptions on the present. Of course for any modern oracle, the past exists not at all.

Today, our greatest oracles are technologists. This is far and away the greatest difference between today and ancient times. Certainly, the Greeks had technology, though they didn't write about it much. It wasn’t in anyway as transformative as the industrial and now information technologies of the last two-centuries. The entire Classical Greek Era rose and declined as agricultural societies. Many tools, particularly those of war, changed from bronze to iron, but over the course of five centuries, daily life for most changed not terribly much. Change overwhelmingly was effected through war, political events, or natural crises such as earthquakes and droughts, thus the oracles' main concern of politics and the judgments of the gods.

In the last two-centuries, societal change has come overwhelmingly from technology, oddly, we remain anciently subjugated to the process. We venerate technologists looking to them as oracles of the future, instead of realizing the technology, not the person, is the only issue. We have no politics or political processes to deal with issues fostered by technology, such as how or even if we should develop any given technology, or accounting any given technology’s long term impacts. We remain largely indifferent, as if it is out of our control, to how society deals with the impacts of technology in our daily lives or upon the greater environment.

Long assigned to history, Delphi remains instructive. We still rely on oracles. We remain largely in the Era of Oprah, politically disconnected individuals, atomized by technology into political impotence. Political value meaninglessly offered in the context of an archaic, broken system.

A democratic renaissance, Greek in nature, would include a politics of technology based not on divination, but education, discussion, participatory implementation, and whole environment accounting. It would require a much more complex participatory system providing continual feedback that can be simultaneously acted on. It would be an evolution of democratic politics, removing power from the prognostications of oracles and back to the hands of the people.