Simone Weil & the Poem of Force

Life in the 21st Century is reader supported, help make it sustainable by subscribing:

I was never aware of Simone Weil until listening to J. Robert Oppenheimer mention her in a speech from 1955. When I first listened to the speech, I should have paid greater attention to Oppenheimer's recognition. Listening to the speech again a couple months ago, I started diving into some of Weil's writings and unsurprisingly found a quite penetrating, non-conventional thinker, grounded in Western history and science.

Raised secular in France, toward the end of her short life, Weil came to appreciate, of all things, Catholicism. Like maenad, Mother Sinead, who Mister Rotten once quipped "liked to wear religions like jewelry," Weil claimed to have at one point been touched by god. Such individuals always prove most dangerous. As she wrote, and Mother Sinead would well have understood, “Ravings about my intelligence have for their aim the avoidance of the question: Does she tell the truth or not? My position of ‘intelligent one’ is like being labeled ‘foolish,’ as are fools. How much more I would prefer their label!”

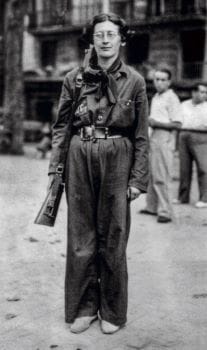

During the civil war, Weil volunteered for the republicans in Spain. As a member of the Durruti Column, her comrades all agreed the best thing she could do for the cause was keep any and all weaponry out of her hands. In 1943, she died in London at the young age of thirty-four. Most of her writing is in pieces, published well after her death. The Iliad or the Poem of Force is an exception. Deserving` a much greater readership than it's ever received, the essay was written and published after the Germans marched into Paris. In today’s era of political desolation, it provides a wellspring for democratic thinking.

One reason she is mentioned by Oppenheimer is she both understood science and its Classical Greek roots. She was one of the few of her era to wrestle with some of the unfolding implications of the great quantum revolution, a revolution that would soon birth nuclear weapons and what may prove even more destructive, the transistor. The essay is a very elemental, radical politics on the question of power bestowed via violence in human relations. In a sublime political device, she defines political force in a physics’ sense, disembodied, recognizable only via its actions, just as Newton postulated force in his three laws of motion. In contemplating gravitational force beyond its revealed actions, that is defining what gravity is, Newton wrote in the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, “hypotheses non fingo”(I do not feign hypotheses). Nonetheless, his equations changed the world.

In her Poem of Force, Weil recognizes force via it actions in human relations. She states her purpose,

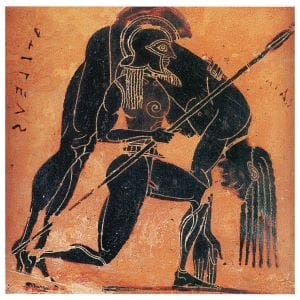

“The true hero, the true subject, the center of the Iliad is force. Force employed by man, force that enslaves man, force before which man’s flesh shrinks away. In this work, at all times, the human spirit is shown as modified by its relations with force, as swept away, blinded, by the very force it imagined it could handle, as deformed by the weight of the force it submits to.”

For a modern world upended by global war she writes,

“For those dreamers who considered that force, thanks to progress, would soon be a thing of the past, the Iliad could appear as an historical document; for others, whose powers of recognition are more acute and who perceive force, today as yesterday, at the very center of human history, the Iliad is the purest and the loveliest of mirrors.”

Next, she gives her political equation of force,

“To define force — it is that x that turns anybody who is subjected to it into a thing. Exercised to the limit, it turns man into a thing in the most literal sense: it makes a corpse out of him. Somebody was here, and the next minute there is nobody here at all; this is a spectacle the Iliad never wearies of showing us:

"The horses rattled the empty chariots through the fields of battle,

Longing for their noble drivers. But they lay on the ground

Dearer to the vultures than to their wives."

"The hero becomes a thing dragged behind a chariot in the dust:

All around, his black hair was spread; in the dust his whole head lay,

That once-charming head; now Zeus had let his enemies defile it on his native soil.”

The terms in her equation strip force of the rationalizing, romanticizing, and celebrating, and well, just the plain bullshit in which the use of force is always draped:

“The bitterness of such a spectacle is offered us absolutely undiluted. No comforting fiction intervenes; no consoling prospect of immortality; and on the hero’s head no washed out halo of patriotism descends.”

This naked recognition of force is best described in the actions of the Iliad’s greatest hero,

Achilles drawing his sharp sword,

Struck through the neck and breastbone.

The two-edged sword sunk home its full length.

The other, face down, lay still,

And the black blood ran out, wetting the ground.

Force “exercised to the limit turns man into a thing in the most literal sense: it makes a corpse out of him.”

Throughout the Iliad force is most recognized by its military application, but Weil understands force and its threat weaves fully through Greek society’s power structures. She writes,

“How much more varied in its processes, how much more surprising in its effects is the other force, the force that does not kill, i.e., that does not kill just yet. It will surely kill, it will possibly kill, or perhaps it merely hangs, poised and ready, over the head of the creature it can kill, at any moment, which is to say at every moment. In whatever aspect, its effect is the same: it turns a man into a stone. From its first property (the ability to turn a human being into a thing by the simple method of killing him) flows another, quite prodigious too in its own way, the ability to turn a human being into a thing while he is still alive. He is alive; he has a soul; and yet — he is a thing.”

She exemplifies this with slavery,

“To lose more than the slave does is impossible, for he loses his whole inner life. A fragment of it he may get back if he sees the possibility of changing his fate, but this is his only hope. Such is the empire of force, as extensive as the empire of nature. Nature, too, when vital needs are at stake, can erase the whole inner life, even the grief of a mother.”

This is a key understanding, equating force to nature, in so doing acknowledging just as homo sapiens are all equal before nature, so we are too in regards to force. As with Newton’s law of motions and gravity, force in political terms equally impacts every person as Newton’s force impacts any mass. In its relation to force, all mass is equal, just as all persons are equally impacted by force. Weil explains this understanding is fundamental to the Iliad and Greek society,

“There may be, unknown to us, other expressions of the extraordinary sense of equity which breathes through the Iliad; certainly it has not been imitated. One is barely aware that the poet is a Greek and not a Trojan.”

She expands on the political physics of force,

“In any case, this poem is a miracle. Its bitterness is the only justifiable bitterness, for it springs from the subjecting of the human spirit to force, that is, in the last analysis, to matter. This subjection is the common lot, although each spirit will bear it differently, in proportion to its own virtue. No one in the Iliad is spared by it, as no one on earth is. No one who succumbs to it is by virtue of this fact regarded with contempt.”

Yet, quite unnaturally, the imposition of force ascribes inequality,

“Perhaps all men, by the very act of being born, are destined to suffer violence; yet this is a truth to which circumstance shuts men’s eyes. The strong are, as a matter of fact, never absolutely strong, nor are the weak absolutely weak, but neither is aware of this. They have in common a refusal to believe that they both belong to the same species: the weak see no relation between themselves and the strong, and vice versa.”

She adds,

“He who does not realize to what extent shifting fortune and necessity hold in subjection every human spirit, cannot regard as fellow-creatures nor love as he loves himself those whom chance separated from him by an abyss. The variety of constraints pressing upon man give rise to the illusion of several distinct species that cannot communicate. Only he who has measured the dominion of force, and knows how not to respect it, is capable of love and justice.”

Wonderfully, three of the greatest political figures of the 20thcentury also understood this. Gandhi’s actions revealed the force necessary for the British to impose their yoke on India. On the new medium of television, King exposed the necessary violence, veiled under the gentil proprieties of apartheid culture, to keep in political, economic, and social chains the descendants of American slavery. And finally, far too little understood, Gorbachev voluntarily dismantled the Soviet empire by his refusal to enact the underlying force that created and kept it together.

Lost to modernity is the recognition in both action and result of force as the great equalizer. “Violence obliterates anybody who feels its touch. It comes to seem just as external to its employer as to its victim. And from this springs the idea of a destiny before which executioner and victim stand equally innocent, before which conquered and conqueror are brothers in the same distress” – a most beautiful recognition of the human condition.

Anybody subjected to force, whether king or slave is turned into a thing. “Force, in the hands of another, exercises over the soul the same tyranny that extreme hunger does; for it possesses, and in perpetuo, the power of life and death. Its rule, moreover, is as cold and hard as the rule of inert matter.”

Again, one reason this piece, the best word is fascinating, is her physics metaphors illuminating politics. Force subjecting the human spirit, turning it to nothing more than matter and the accompanying loss of spirit, of life, is the foundation of Greek tragedy. It is this sense of tragedy completely lost to modernity. Weil explains:

“Attic tragedy, or at any rate the tragedy of Aeschylus and Sophocles, is the true continuation of the epic. The conception of justice enlightens it, without ever directly intervening in it; here force appears in its coldness and hardness, always attended by effects from whose fatality neither those who use it nor those who suffer it can escape; here the shame of the coerced spirit is neither disguised, nor enveloped in facile pity, nor held up to scorn; here more than one spirit bruised and degraded by misfortune is offered for our admiration.”

Misfortune, fate, or the gods were all the same thing for the Greeks. “Victory is less a matter of valor than of blind destiny which is symbolized in the poem by Zeus’s golden scales,”

“Then Zeus the father took his golden scales,

In them he put the two fates of death that cuts down all men,

One for the Trojans, tamers of horses, one for the bronze-sheathed Greeks.

He seized the scales by the middle; it was the fatal day of Greece that sank.”

Essential to understanding the Greeks, particularly their development of democracy, is the fundamental ethos of the equality of homo sapiens in their confrontation with force and nature. In regards to force, “conquered and conqueror are brothers in the same distress.” Only with this understanding, this tragedy, can anyone hope to be truly human.

For the Greeks, man can only be comprehended as a social animal and this is fundamental to Weil’s reading of the Iliad. No one, no action stands or suffers alone. Only man as a political animal, can Newton’s third law, that every action has an equal and opposite reaction, be used as political metaphor. She writes,

“Force is as pitiless to the man who possesses it, or thinks he does, as it is to its victims; the second it crushes, the first it intoxicates. The truth is, nobody really possesses it. The human race is not divided up, in the Iliad, into conquered persons, slaves, suppliants, on the one hand, and conquerors and chiefs on the other. In this poem there is not a single man who does not at one time or another have to bow his neck to force.”

She adds, “These men, wielding power, have no suspicion of the fact that the consequences of their deeds will at length come home to them — they too will bow the neck in their turn.”

Most importantly, Weil writes of the reaction following any use of force ,

“This retribution, which has a geometrical rigor, which operates automatically to penalize the abuse of force, was the main subject of Greek thought. It is the soul of the epic. Under the name of Nemesis, it functions as the mainspring of Aeschylus’s tragedies. To the Pythagoreans, to Socrates and Plato, it was the jumping-off point of speculation upon the nature of man and the universe.”

This idea of retribution, what Weil later compares to the eastern notion of karma, which she suggests came from the Greeks, is only understandable in context of man as a political animal. By her literal disembodying force, it takes on characteristics of Newtonian physics, specifically the third law – for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.

This may be hardest for the present age to understand, yet soon after she wrote, how true it would prove for the Germans. In today’s United States any such understanding would be snickered at and loudly refuted by the CEOs of leviathan corporations and financial institutions. Force underlies all their power, though in so many ways their actions are shielded from its direct reactions. In the last two centuries, what force turns humanity into a “thing” more than a life being no more than a politically disenfranchised cog in the great industrial production and consumption machine. The same too can be said for force’s instigators in America’s National Security State, who for 75 years have been shielded from both their actions and its blowback. Domestically, the ethos of equality in America withers away, globally, despite the proclamation of universal equality in the republic's founding declaration, it rarely existed toward the rest of the world.

Force is in and of itself an elixir, an intoxicant only moderated by reflection:

“The man who is the possessor of force seems to walk through a non-resistant element; in the human substance that surrounds him nothing has the power to interpose, between the impulse and the act, the tiny interval that is reflection.”

“Where there is no room for reflection, there is none either for justice or prudence. Hence we see men in arms behaving harshly and madly. We see their sword bury itself in the breast of a disarmed enemy who is in the very act of pleading at their knees. We see them triumph over a dying man by describing to him the outrages his corpse will endure. We see Achilles cut the throats of twelve Trojan boys on the funeral pyre of Patroclus as naturally as we cut flowers for a grave.”

It is in a functioning democracy, political reflection on the use of force, instilled via accountability, may best be realized. It is no coincidence the Greek culture that conceived tragedy and the recognition and appreciation of human equality in regards to tragedy, also created democracy. In Athens, force was embodied in its institutions, accountability keeping it in check. Power held deliberately accountable is essential to democracy. In democracy power is fluid, no individual long possesses it. In Athens, all offices were elected or chosen by lot annually. Any exercise of democratic power was held directly accountable in many ways. With accountability, democratic action immediately induces democratic reaction. With democracy, force is humanized through collective reflection.

The only weapon humanity holds against the seduction of force is reflective thought. It matters not which side you advocate, force eventually greets the strong and weak with equal fate. “By its very blindness, destiny establishes a kind of justice. Blind also is she who decrees to warriors punishment in kind. He that takes the sword, will perish by the sword. The Iliad formulated the principle long before the Gospels did, and in almost the same terms, “Ares is just, and kills those who kill.”

Now, this is an interesting and correct point, the impact of Greek thought on Christian thought. It is little appreciated the Greeks controlled the biblical lands for three centuries before the life of the Christ, itself a Greek title meaning “anointed.” Certainly, Greek thought was transmuted through the Gospels. Three and half centuries later, the Latin Church's greatest intellectual pillar, Augustine, even thought he recognized an ancient Christian in Plato.

The Gospels were all originally written in Greek, which at the time was the lingua franca of many of the educated across the Eastern Mediterranean. There’s long been conjecture John was Greek, after all who but a Greek could write, “In the beginning was the word.”

The Gospel of John is also responsible for maybe the only joke in a book fairly bereft of humor. It comes from Pilate. The Romans controlled Jerusalem for less than a century at the point of the very Roman crucifixion. Accused of claiming kingship and even of being a god, dumbfounded by his charge, Pilate has the anointed scourged and crowned with thorns. Afterwards, Pilate places the tormented Christ in front of his persecutors pronouncing, “Ecce Homo”(Behold the Man). In the often brutal humor of both the Romans and Greeks, Pilate’s statement was without doubt wry.

Certainly Nietzsche, who used Ecce Homo for the title of his often amusing auto-biography got the joke. Weil certainly reveals Nietzsche’s influence writing, “In spite of the brief intoxication induced at the time of the Renaissance by the discovery of Greek literature, there has been, during the course of twenty centuries, no revival of the Greek genius. ...the spirit that was transmitted from the Iliad to the Gospels by way of the tragic poets never jumped the borders of Greek civilization; once Greece was destroyed, nothing remained of this spirit but pale reflections.”

And he’d find great humor in, “Throughout twenty centuries of Christianity, the Romans and the Hebrews have been admired, read, imitated, both in deed and word; their masterpieces have yielded an appropriate quotation every time anybody had a crime he wanted to justify.”

Though no doubt he’d have great trouble with “The Gospels are the last marvelous expression of the Greek genius, as the Iliad is the first.” Weil looked at the Passion as the great plot of Greek tragedy in the gospels, force applying its universal equality, where “a divine spirit, incarnate, is changed by misfortune, trembles before suffering and death, feels itself, in the depths of its agony, to be cut off from man and God.”

Weil no ordinary Christian, and certainly like Mother Sinead no average Catholic, concludes,

“Those who believe that God himself, once he became man, could not face the harshness of destiny without a long tremor of anguish, should have understood that the only people who can give the impression of having risen to a higher plane, who seem superior to ordinary human misery, are the people who resort to the aids of illusion, exaltation, fanaticism, to conceal the harshness of destiny from their own eyes. The man who does not wear the armor of the lie cannot experience force without being touched by it to the very soul.”

Any conception of force as the great tragic equalizer was lost to the Christian West in its dealings with the world as the “practice of forcible proselytization threw a veil over the effects of force on the souls of those who used it.”

“The Occident, however, has lost it, and no longer even has a word to express it in any of its languages: conceptions of limit, measure, equilibrium, which ought to determine the conduct of life are, in the West, restricted to a servile function in the vocabulary of technics. We are only geometricians of matter; the Greeks were, first of all, geometricians in their apprenticeship to virtue.”

Over the the last half-century, virtue was found to only be an unneeded concern of old dead white men. Technics, technology has become the great force of modernity, unrestrained by collective reflection. Whether across society and the environment we are all part, technology's actions and resulting reactions politically disregarded or unrecognized,

Weil concludes,

“Nothing the peoples of Europe have produced is worth the first known poem that appeared among them. Perhaps they will yet rediscover the epic genius, when they learn that there is no refuge from fate, learn not to admire force, not to hate the enemy, nor to scorn the unfortunate. How soon this will happen is another question.”

In America, a land of illusion, exaltation, and fanaticism, enshielded by the armor of the lie, a juvenile ethos of progress justifies technological force, any notions of human equity jettisoned as unworthy or certainly unprofitable. A little less than a century ago, in a world cascading into force's bloody vortex, a young, extraordinary, French woman showed the Iliad to be as relevant a guide to equity in her day as it is to ours.

Life in the 21st Century is reader supporter, help make it sustainable:

Good translations of the Iliad are few. I always found attempts to keep poetic structure sort of ridiculous, unreadable anyway. A few years ago, John Dolan, who has spent many years measuring the dominion of force, came out with an interesting and funny interpretation.