The Book and the Screen

In Tocqueville's Ancien Regime there’s an excellent chapter titled, “How around the middle of the eighteenth century men of letters became the leading political figures in the country and the consequences of this.” It's a wonderful explanation of the unequaled importance books and their authors played in the French Revolution. Anyone with elementary knowledge of the times can quickly begin a list of the authors including, Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquieu, the list is long. Most enchanting, Tocqueville places the fundamental catalyst for the Revolution in the authors' pens.

Tocqueville writes,

“All the spirit of political opposition aroused by the failings of government had taken refuge in literature since it could not thrive in public affairs. Writers had become the authentic leaders of that great gathering which leaned towards demolition of the social and political institutions of the country.”

Before this chapter, Tocqueville spends two-thirds of the book explaining the long deterioration and increasing failure of French government and politics. 18th century France saw the disenfranchisement of the old feudal nobility, who were gradually stripped of responsibility but gathered ever greater privileges, the complete isolation of the peasantry, and the total centralization of government power under a rapacious crown. He explains,

“Now when you think that this same French nation so alienated from its own affairs, so deprived of experience, so hindered by its own institutions and so helpless to reform them was, at the same time, of all nations on earth, the most literary and the most fond of intellectual things, you will easily realize how writers became a political influence at that time and ended by being the most important.”

He continues,

“All men chafing from the daily practice of legislation soon fell in love with this literary form of politics. The taste for it affected even those whose nature and social position naturally kept them as far away as possible from abstract speculations. Not a single taxpayer bruised by the uneven distribution of the taille (tax) was not warmed by the idea that all men should be equal; any small landowner stripped bare by an aristocratic neighbor's rabbits was pleased to hear that every kind of privilege without exception was condemned by reason. Each public enthusiasm was thus cloaked in philosophy; public life was forced into literature. Writers took hold of public opinion and found themselves for a time occupying the position which party leaders usually occupied in free countries.”

The political ascendance of the writer was brought about not only by the failure of established politics, but just as importantly the rise of the influence of the book/pamphlet. Over the last several centuries, feudal institutions and customs had degraded and became politically disenfranchised. The rise of the book occurred with and helped cause this decline. The book, the product of the printing press, was a post-feudal technology.

Tocqueville describes the political decline and the resulting reaction,

“On seeing so many bizarre and disordered institutions – the offspring of other eras – which seemed bound to live forever even when they lost their value, writers readily conceived a distaste for ancient ways and tradition and were naturally drawn to a desire to rebuild the society of their time following an entirely new plan which each of them traced by the light of his reason alone.”

The Ancien Regime records the impotence of French politics as an entirely inert force. “A French nation so alienated from its own affairs, so deprived of experience, so hindered by its own institutions and so helpless to reform.” A situation not far in the distance for American politics. Into this void the writer stepped, not so much by acclaim, as necessity.

Across the globe, the book helped play a defining political role for the next two centuries. Yet in 21st century America, books and writers are politically inconsequential. In the last fifty years, you'd be hard pressed to name a book or writer that has consequentially impacted politics, in the last two decades, not one.

This is neither a fault of the books or writers. I can immediately name a couple excellent books just in the last half dozen years, Yasha Levine's Surveillance Valley and Alexander Zaitchik's Owning the Sun that should be widely influential in the creation of any consequential political thinking for the 21st century. Both disappeared almost as quickly as they were published. The reason the book no longer influences politics is twofold; first, just as with the 18th century France, the decline of anything that can be considered healthy politics, secondly, the screen's conquest of the book.

The screen is a new invention, not much more than a century old compared to the seven century history of the printing press. The screen was introduced with the invention of film. It was projected upon, a collective experience of hundreds seated in theaters. Fifty years later, with television, the screen inverted. The screen itself and the collective viewing experience shrunk in size moving from theaters to homes. However, thanks to broadcast technology, audiences could simultaneously be tens of millions people scattered across family rooms in millions of homes. In the last two decades, screens have shrunk to fit into a pocket, the experience shrinking to one person connected to a continuous and might as well be considered infinite data stream capable of being tapped at the individual's discretion.

While the screen can be a text medium, as anyone reading this can attest, it is much more powerful medium of images and attached sound. The screen has not simply displaced the book's political role but trampled it. Interestingly, despite the screen's illusion of total immersion in the world, it has created an Ancien Regime politics where individuals have “no connection with that world nor can they see what others are doing in it” and “lack the obvious education which the sight of a free society and the news of what is happening give even to those with the least contact with government.”

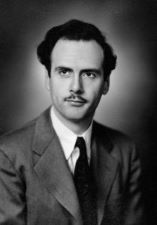

Despoiling the politics preceding it, the screen created personalities. Personality isn't politics, but personalities can be marketed. A half-century ago, the great technology historian Marshall McLuhan made an astute observation on the screen’s development and society, “Full awareness of this technological change had dawned on Madison Avenue ten years ago when it shifted its tactics from the promotion of the individual product to the collective involvement in the ‘corporate image.'"

This has become the social aspect of the screen, individual personality/image as corporatized product, defined collectively through the use of the tools of business, mainly marketing and advertising. Tocqueville wrote, “Writers took hold of public opinion and found themselves for a time occupying the position which party leaders usually occupied in free countries.” Today, the screen is the only party, comprised of partisanly marketed personalities/images. Organization, the fundamental element of all effective politics, is simply the screen, the organization behind the personalities politically ignored.

The 18th century book, their writers, and their ideas helped overthrow the Ancien Regime, but failed entirely in creating a new French political order. The same books, writers, and ideas simultaneously helped shape the new American republic. There's many reasons for this, deserving a book themselves, but one very important reason just as important for this age, the American revolutionaries were never “contemptuous of ancient wisdom and still more inclined to trust their own reason.” The American revolutionaries were steeped in historical knowledge. The democratic histories of Ancient Athens and Rome was wisdom they sought to enshrine in building a new age of politics. At its founding, the American republic, unlike the French, did not claim to abolish the past and proclaim a new Year 1. Today’s Silicon Valley tech revolutionaries have more in common with 1789 Paris than 1776 Philadelphia.

The Ancien Regime of France was overthrown by the book and the book shaped the modern world. McLuhan writes,

“….typographic technology, applied not only to the rationalizing of the entire procedures of production and marketing, but to law and education and city planning, as well. The principles of continuity, uniformity, and repeatability derived from print technology have, in England and America, long permeated every phase of communal life.”

He adds, “Literacy is indispensable for habits of uniformity at all times and places. Above all, it is needed for the workability of price systems and markets.” The screen is now in the process of overthrowing all this, text has not disappeared, but fitfully survives on the screen, increasingly only as a select medium of power. As McLuhan writes, “the screen child encounters the world in a spirit antithetic to literacy.” It is immensely ironic that for two centuries, the republican revolutions across the globe called in unison for universal literacy, while the first modern republic, America, experiences the dominance of the screen and the displacement of literacy as any sort of political medium.

To in any way confront this reality requires first and foremost an understanding it is happening. In 21st century America, the screen has destroyed established politics as thoroughly as the book helped overthrow France's 18th century Ancien Regime. The impulses of those controlling the organization behind the screen are not in anyway republican, but Napoleonic. Understanding the screen and figuring out how to incorporate it into a healthy politics is fundamental for any notions of democracy in the 21st century.