The Land Ethic and Politics of Technology

Aldo Leopold was one of the first ecologists. Environment and ecology are terms used synonymously, however environment is a more encompassing term, dealing with all physical aspects of any given surrounding. Ecology defines the systemic interactions of biological organisms within a larger environment. Characteristics of any ecological system are very much defined by the greater environment in which it is found. For example, the ecology of a mountain meadow is in part defined by the greater environment of the mountain, such as the altitude, just as the teeming life of a tropical forest is shaped by sun and rain.

Biology, the study of life, is a relatively new science, especially in relation to physics. Certain understandings of biology have been around for thousands of years, but physics as a recognized school of thought and a societal shaping force has had much greater impact over the last five centuries. Such influence by biological science is not much older than a century.

Detrimentally, biology is still too often defined by the conventions of physics, distorting the understanding available with our growing knowledge of ecologies. Physics endlessly divides, seeking fundamental particles and their motion to define everything on top. In certain very important ways, ecological understanding is just the opposite. Any single organism cannot truly be understood without understanding how it interacts with the greater ecological system within which it evolved. Reductionist and determinist analysis, physics, is still very common in looking at ecological systems, yet such thinking alone fails in understanding that knowing any given organism must take into account the greater ecological system by which it was formed.

In 1949, Leopold was one of the first to put forth ecological thinking with his wonderful book, A Sand County Almanac. He had spent a lifetime working for the US Forest Service, learning the intricacies of forests and other ecological systems. The book is an essential look not from a physics’ perspective of deterministic particles, but a look at whole systems – the perpetual interactions of countless multitudes of individual organisms creating a larger ecological system, and in return, this greater ecological system's affect on each individual organism.

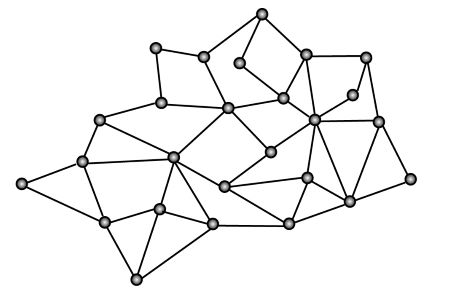

Leopold offers some excellent ideas for understanding ecology. Tellingly he still uses what was then and very much still the established practiced of describing ecological complexity as a pyramid, a practice derived from physics. In a world turned upside down by Darwin, pyramids helped continue the wrong-headed notion of human ecological dominance. Today, it is essential to consider ecological systems as distributed networks, webs without centers. Leopold writes,

“Man is one of thousands of accretions to the height and complexity of the (ecological) pyramid. Science has given us many doubts, but it has given us at least one certainty: the trend of evolution is to elaborate and diversify the biota (the biota being the entirety of biological organisms).”

Here, Leopold comments in opposition to the anti-evolutionary results of modern industrial agriculture, which results in the homogenization of ecologies. He then offers a critique of the education system in continuing to limit this understanding, a critique just as relevant today,

“One of the requisites for an ecological comprehension of land is an understanding of ecology, and this is by no means co-extensive with 'education'; in fact, much higher education seems deliberately to avoid ecological concepts. An understanding of ecology does not necessarily originate in courses bearing ecological labels; it is quite as likely to be labeled geography, botany, agronomy, history, or economics. This is as it should be, but whatever the label, ecological training is scarce.”

Leopold is explaining the “division of intellect.” While the division of labor began with the Agrarian revolution 10,000 years ago, the division of intellect became acute with modernity and an ever more increasingly a barrier to allowing the healthy utilization of the recent knowledge gained by science and the tsunami of information generated by our newest technologies.

In the last chapter of the book, “The Land Ethic,” Leopold looks at the practices of industrial farming and its massive impact on established ecologies. He starts with a fundamental insight of the politics of technology,

“The complexity of co-operative mechanisms has increased with population density, and with the efficiency of tools. It was simpler, for example, to define the anti-social uses of sticks and stones in the days of the mastodons than of bullets and billboards in the age of motors…. Man' s invention of tools has enabled him to make changes of unprecedented violence, rapidity, and scope.”

In looking at Homo sapiens historical relation to the land, Leopold writes,

“There is as yet no ethic dealing with man's relation to land and to the animals and plants which grow upon it. Land, like Odysseus' slave-girls, is still property. The land-relation is still strictly economic, entailing privileges but not obligations.”

Just as humankind ethically evolved – with a long way to go – our relations to each other, for example, slavery is no longer acceptable, we need to develop an ethic for our relations to the land and its ecologies. Such an ethic is “an evolutionary possibility and an ecological necessity.”

He continues,

“All ethics so far evolved rest upon a single premise that the individual is a member of a community of interdependent parts. His instincts prompt him to compete for his place in that community, but his ethics prompt him also to co-operate (perhaps in order that there may be a place to compete for). The land ethic simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land.”

“…In short, a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members, and also respect for the community as such.”

Life in the 21st Century is a reader-supported publication. Please become a paid subscriber.

Leopold critiques the conservation politics his era, which unfortunately can still describe most of today's,

“Despite nearly a century of propaganda, conservation still proceeds at a snail's pace; progress still consists largely of letterhead pieties and convention oratory. On the back forty we still slip two steps backward for each forward stride. The usual answer to this dilemma is 'more conservation education.'”

He adds a completely accurate knock on all environmental and really all present politics,

“The usual answer to this dilemma is 'more conservation education.' No one will debate this, but is it certain that only the volume of education needs stepping up? Is something lacking in the content as well? It is difficult to give a fair summary of its content in brief form, but, as I understand it, the content is substantially this: obey the law, vote right, join some organizations, and practice what conservation is profitable on your own land; the government will do the rest. Is not this formula too easy to accomplish anything worth-while? It defines no right or wrong, assigns no obligation, calls for no sacrifice, implies no change in the current philosophy of values. In respect of land use, it urges only enlightened self-interest. Just how far will such education take us?”

He then rightly concludes,

“To sum up: a system of conservation based solely on economic self-interest is hopelessly lopsided. It tends to ignore, and thus eventually to eliminate, many elements in the land community that lack commercial value, but that are (as far as we know) essential to its healthy functioning. It assumes, falsely, I think, that the economic parts of the biotic clock will function without the uneconomic parts. It tends to relegate to government many functions eventually too large, too complex, or too widely dispersed to be performed by government.”

In opposition he writes,

“A land ethic, then, reflects the existence of an ecological conscience, and this in turn reflects a conviction of individual responsibility for the health of the land. Health is the capacity of the land for self-renewal. Conservation is our effort to understand and preserve this capacity.”

To creating such an ethic, Leopold hits directly at the greatest established impediment, established economics, which can be considered similar to the values held by the slave-holders of the past and their inability to rid themselves of that “peculiar institution.” He writes,

“It of course goes without saying that economic feasibility limits the tether of what can or cannot be done for land. It always has and it always will. The fallacy the economic determinists have tied around our collective neck, and which we now need to cast off, is the belief that economics determines all land use. This is simply not true. An innumerable host of actions and attitudes, comprising perhaps the bulk of all land relations, is determined by the land-users' tastes and predilections, rather than by his purse. The bulk of all land relations hinges on investments of time, forethought, skill, and faith rather than on investments of cash. As a land-user thinketh, so is he.”

This is not a fallacy economic determinism has tied around the necks of land use alone, but society as a whole. Leopold adds,

“…to release the evolutionary process for an ethic is simply this: quit thinking about decent land-use as solely an economic problem. Examine each question in terms of what is ethically and esthetically right, as well as what is economically expedient. A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community.”

These last two ideas are essential to developing not only a land ethic, but also a politics of technology. As stated in a recent piece on money, we need to supplant money as the dominant information and communication medium of human social ecology. This need arises not just from the last decades’ critical devaluing of money as any valuable information medium, but the essential need to transcend money’s long established limitations.

Leopold states “the bulk of all land relations hinges on investments of time, forethought, skill and faith rather than on investments of cash,” thus arises the need for information media measuring such values without having to first transform them into crude money relations, that are increasingly controlled by fewer, more clueless, entrenched interests. More complex valuing systems require more than new technologies, but establishing new and maybe reestablishing some old human associations, organizations, and communication processes, particularly in regards to measuring ethical and esthetic worth.

In turn, developing a land ethic requires new ethics for dealing with each other. In the most fundamental understanding of ecology, the parts help define the whole, while the whole in return helps shape each part.