The Last Bolshevik (Part 1)

Thank you for reading Life in the 21st Century. This post is public so feel free to share it so readership will grow.

“Only a great genius can save a prince who undertakes to alleviate the lot of his subjects after a lengthy period of oppression. Evils which are patiently endured when they seem inevitable become intolerable once the idea of escape from them is suggested.” – Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old Regime and the Revolution

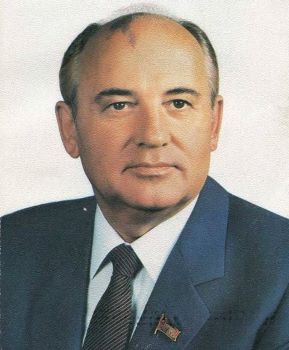

The historical legacy of Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev is complicated and not well understood. With any figure whose life massively impacts the world, it is sometimes difficult to understand the person and their actions, especially as both sanctifying adulators and belittling detractors pick and scatter the bones. What's fascinating about Gorbachev is in some ways he's better understood, though dismissed, by his detractors than by those who praise him. One undeniable fact, in six brief years, Gorbachev changed the world.

Amusing and revealing, Gorbachev sycophants are almost all non-Russians, largely of European and American variety, who both then and now fail to understand Gorbachev's actions and thinking. Despite all the praise, faced with similar challenges, few of Gorbachev's public champions would follow his path as many have proved time and again.

Gorbachev's detractors are overwhelmingly Russian, in fact the vast majority of Russians. Here again Gorbachev's thinking and actions are not greatly understood. When presented with the opportunities Gorbachev unleashed, the majority were incapable of meeting them, unlike the Ancient Greeks under Solon and Cleisthenes, instead they became victims of an entirely nefarious, covetous, and cunning few.

Two books, (thanks to Ames), spell out this dichotomy or, for the hopelessly confused, the dialectic. The first book is last year's Collapse, by Russian Vladislav M. Zubok. This is an excellent work. It's only drawback, the occasional cheap shots emanating from Zubok's disagreement with Gorbachev's actions. While you certainly can disagree with his actions, political ineptitude was not a fault of Mikhail Sergeyevich.

The other book, Russia's Path from Gorbachev to Putin (2007) written by two Americans, David M. Kotz and Fred Weir, thus, appropriately sympathetic to Gorbachev. Kotz's and Weir's book has more historical context and continues the story after Gorbachev is pushed from power. Here the book is best, reporting the massively destructive, devastating, and completely incompetent American backed Yeltsin years that led to Putin's ascension. As a chronicle of the Gorbachev years, Zubok's book is far more encompassing and engrossing.

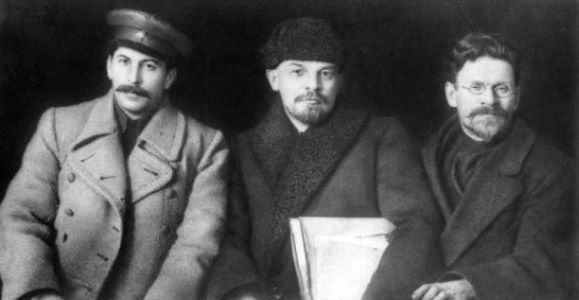

To understand Gorbachev, it is imperative to understand the Soviet Union and indeed the Russia that preceded it. The Soviet Union quickly emerged out of the overthrow of the centuries rule of the Russian Czars. From the Latin Caesar, the Czars ruled like all European and Asian monarchies – horrendously centralized, top-down, stifling control by a small elite. In the first two decades of the 20th century as the House of the Romanov shook and fell, Russia was overwhelmingly an agrarian society. The Czars' version of slavery – serfdom – subjecting the vast majority of the Russian people had only officially ended a half-century before the revolution

Russian industrialization was limited, nowhere as extensive as then global industrial leaders Germany, Britain, United States, and Japan. So, it's always been curious that agrarian Russia became the first country attempting to prove the fatally flawed, though always in certain ways insightful, industrial political musings of Karl Marx. According to Bolshevik Marxism, in a matter of months, Russia passed from monarchy to bourgeois republicanism and then to a completely undefined and existentially problematic notion of something deemed “socialism.”

The resulting bastardized synthesis is best represented in the new state's adopted name, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Republic represented the modern republican era initiated with the founding of the United States. Socialist was meant to signify an ongoing transition from capitalism to a vaguely defined future communism. Soviet was the wildcard and in retrospect the most interesting, and in every way the most historically exceptional.

The soviets were spontaneously organized associations of farmers and workers that sprouted across revolutionary Russia, instigating the February Revolution and ending the rule of the Czar in 1917. The soviets’ appearance was something never expected in either Marx's historical or Lenin's revolutionary theories. However, it was Lenin's genius, and certainly it can be called that, to use the soviets to gain control of the state seven months later with the October Revolution. “All power to the Soviets,” became the Bolsheviks' battle cry on the street with the party's vanguard overthrowing the “bourgeois” Provisional Government established in February.

Zubok states Lenin's writings became the lodestone for Gorbachev in his moves to reform the Soviet system. Just as you could correctly say the 1917 October Revolution founding the Soviet Union was very much the work of one man – Lenin – so too was Gorbachev's Revolution, leading inadvertently and always for Gorbachev, undesirably to the Union's dissolution.

Lenin was a revolutionary. His writings overwhelmingly concern organizing revolt. Almost all pre-Soviet Bolshevik writings concentrated on this one topic, along with endlessly expressing a misguided faith they were part of some inevitable and irresistible historical force evangelized by Marx's cockeyed science of “dialectical materialism.”

Ascending to power, then for several more years fighting a civil war pushed by domestic and foreign foes, Lenin was allowed little time to think or begin establishing any sort of new order before his death. The system Gorbachev faced and sought to reform was overwhelming created by Lenin's successor, Joseph Stalin, who brutally ruled for 30 years shaping the Soviet system. The system Gorbachev rose to the top was as centralized and in many ways as oppressive as the Czars.

As a revolutionary organization created under a brutal tyranny, the Bolsheviks relied on secrecy, heavily guarded communication, and centralized control, all political procedures antithetical to modern bourgeois republicanism. All were entrenched habits that proved extremely pernicious when instituted into the Soviet state. Egregiously centrally commanded, all information and communication was tightly controlled. The entire system restrictively wrapped in a certain egalitarian ethos and practices.

Stalin did quickly industrialize the Soviet Union, which says much about what we refuse to learn about the processes of industrialization, China being the most recent example. Industrialization never required functioning, modern republican structures.

In the 1960s, the entire system began to stagnate. By the early 80s, a growing segment of the leadership realized reform was necessary. With a reform mandate, Gorbachev became Premier of the Soviet Union in 1985. Zubok's book is an excellent blow by blow chronicle of the next six years.

Upon taking office, Gorbachev immediately commenced reform. The twin pillars of Gorbachev's reforms were glasnost and perestroika. Glasnost was the opening of thought, information, and communication. Perestroika concerned restructuring the economy and political system. Gorbachev stated, “The essence of perestroika lies in the fact that it unites socialism with democracy.”

Political and government power in the Soviet Union lay exclusively with the Communist Party, not with the state. Zubok describes the Party's organizational power,

“The CPSU was the only organized force across the whole Soviet Union. The Party’s hierarchical organization of 15 million members included cells in every unit of the armed forces, the police, economic ministries, educational institutions, and cultural organizations. In many republics and outlying Russian regions, local Party committees remained intimately connected with the bureaucracy and economic management.”

Gorbachev instantly began reorganizing the Party, replacing the old guard at the top largely by convincing them to retire, and creating new institutions over which the Party had no control. These institutions were organizationally decentralized, bottom-up control. Maybe the most incredible thing about Gorbachev was his understanding Jefferson's imperative that democracy, all democracy, is distributedly organized.

Democratic tradition, outside the brief vibrancy of the soviets during the revolution, was entirely absent from the millennium Russian experience. Not that Russia was anyway exceptional in this. Across the recorded histories of Europe, Asia, and the entire globe, democracy has been the exception. Even today, the modern republican era has forgotten more than it remembers about democracy, most tragically in its American birthplace.

In addition, the established Russian industrial infrastructure, all centrally controlled and only decades old, created its own significant obstacles to change. This entrenched industrial infrastructure played a large, little understood, or studied role in the Russian people's inability to meet Gorbachev's democratic reforms, again, unlike the agrarian Ancient Greeks who rose to meet similar opportunity.

One of the first actions Gorbachev enacted immediately exposed the problems of loosening centralized control of industry and restructuring a more distributed order. To lift stagnation in the economic order, the reformers placed new “quality control inspectors” in plants across the economy. These inspectors were not top-down controlled by the Party, but allowed to follow their own and the plant's initiatives. However, even this limited loosening of command and control instantly began breaking the cogs and clogging the gears of the massive Soviet industrial machine.

Combined with other initial reforms, Zubok writes,

“Even the best Soviet plants, built by Western companies in the 1960s, suddenly faced default. The end to the supply of many products, of whatever quality, affected entire economic chains of distribution: the lack of components and parts meant that many assembly lines came to a screeching halt. This was another example of how a sudden corrective measure, even well justified, could lead to inevitable economic collapse.”

Over the next six years, democratic political and economic reform met the same obstacles, simply, the breaking of centralized control without corresponding immediate gain from a newly forming distributed order. This is where Zubok is especially unfair to Gorbachev writing things like, Gorbachev “fumed and dawdled, or quoting others that Gorbachev was politically inept, “speaking tactlessly and revealing his weak hand.”

No one understanding the Soviet Union Gorbachev rose to the top of and then his six years of what can only be called revolutionary reform could in anyway imply Gorbachev dawdled or was weak. He was one of the most talented political figures of the 20th century. Does that mean he did everything right, absolutely not. They were traveling a political landscape without a well defined map, and indeed, the Gorbachev Revolution ended in many ways opposite the direction he sought. Well, welcome to the history of revolution.

What Zubok and many of Gorbachev's detractors get most wrong, or more accurately, can't accept, is Gorbachev's refusal to revive authoritarian control and even more historically radical, rejecting the use of violence to hold together a system that it was quickly becoming apparent remained entirely reliant on violence.

Zubok scolds, “Gorbachev could have appointed a ruling economic junta with emergency rights.” The only way this could be done is by use of force. Zubok mostly refuses to address the issue, though at one point complains Gorbachev and much of his generation had become soft on the use of force – such petty tyrants we can all be!

However, he does provide Gorbachev's enlightened view on the matter,

“Gorbachev vowed to Shakhnazarov (one of his aides) that he would never rule by decree. Nobody, including the Supreme Soviet, and the forthcoming Congress of People’s Deputies, he declared, 'can force me into dictatorship. I would rather resign . . . This is a firm conviction, a life-long principle.'”

This was not political ineptitude, incompetence, or dawdling, just the opposite, a political conviction or better a political aesthetic historically exceptional for a person in his position of power. Gorbachev's deliberate choice to not use violence to renew the Soviet dictatorship or hold together the empire was an historically unprecedented and intentional act of strength, made time and again by a man who well understood the great technological, environmental, and political challenges humanity faced would be met neither through violence or dictatorship – a lesson Europe's and the world's present truly failed political leadership now tragically rush to learn.

Part II — Fated with destructive partners

You can share Life in the 21st Century via: Reddit, Twitter, Facebook

Life in the 21st Century is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.