The Politics of Ape & Machine: Power as Organization

“The most difficult political problem facing mankind is the centralization of power in highly technological societies.” - Lawrence Goodwyn, Democratic Promise, 1976

“There will be a further increase of useful things for useless people.” – Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality, 1970

“It is quite conceivable that the modern age―which began with such an unprecedented and promising outburst of human activity―may end in the deadliest, most sterile passivity history has ever known.” - Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, 1956

Homo sapiens evolved as social animals. From our beginnings, people lived and survived collectively as organized units, whether family, tribe, community, city-state, nation, empire or a combination of all. The identity of every human individual who ever lived was defined through the social organization they were part. With social organization power is defined. Without social organization, any individual, whether Pharaoh or CEO, is simply an individual. Only by understanding social organization in all its configurations – political, economic, cultural, and technological – do we derive any ability to understand power. The understanding of power as organization is the most fundamental politics.

In today's politics the concepts, structures, and processes of social organization are largely absent. There are numerous reasons for this void of organizational understanding. Most importantly, established power always seeks to obscure or outright prohibit thinking about the organization that upholds their power. All power requires acceptance of the organization it is based either through voluntary acquiescence or force. Discussion of alternative structures and processes is basically haram. Accepted politics in any given power structure always falls short of challenging the organization of power itself.

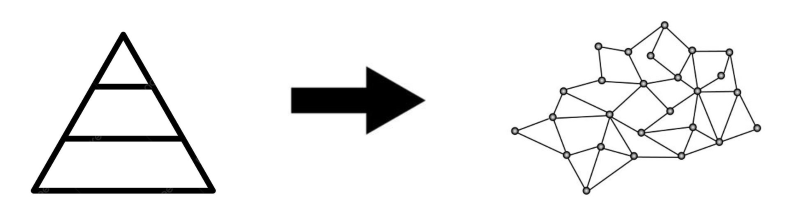

Much political history and understanding could be helpfully rewritten with a profoundly simple look at the actual structural organization of power, whether it's political, cultural, or economic. With the still relevant categories of the Ancient Greeks, the organization of power conforms to geometric patterns. Centralized, hierarchical power — oligarchy, monarchy, and tyranny — all take the shape of a pyramid. Power is concentrated with a few at the top, vertically spreading down to a powerless mass base. Decision making and the ability to act, power, is concentrated at the top.

Democracy is more unwieldy, horizontally organized. Power is distributed. Decision making and resulting action partially resides with each individual member of an organization, but the greatest power resides with the decisions and actions taken collectively. Democracy cannot be conducted through centrally organized power, nor can tyranny be afflicted through distributed power.

Across recorded history, centralized hierarchical order has overwhelmingly been the rule, distributed democratic order the exception. Hierarchical centralized organization is humanity’s accepted traditional norm. Historically, discussion of any alternative or even the ability to conceive of alternatives largely absent.

By questioning the organization of power, power itself is questioned. The history of the United States provided a number of exceptions to the simple historical acceptance of hierarchical order, including the founding’s establishment of modern republicanism. Far too often overlooked is the Populist Era at the end of the 19th century. One of American history's profoundest democratic discussions about the organization of power was conducted by the Populists. They experienced the end of the distributed agrarian republic, replaced by the centralized industrial corporate state of today. Politically, the distributed democratic power of the yeoman farm and its numerous associations were replaced by the concentrated, centralized, oligarchical power of the industrial mega-corporation.

Inherently, industrialization is consolidation. It is the consolidation of resources, energy, and labor. Looking at industrialization's brief two century history, its organization has fostered centralized power structures whether in the United States, Germany, the Soviet Union, or most recently China. However, unlike the other three, American industrialization grew out of what had been a brief but significant distributed political order. The Populists were an organized movement who understood industrialization was ripping power from their hands.

In Democratic Promise, seminal democratic historian Lawrence Goodwyn writes,

“Populists dissented against the progressive society that was emerging in the 1890’s because they thought that the mature corporate state would, unless restructured, erode the democratic promise of America. Not illogically, therefore, they sought to redesign certain central components in the edifice of American capitalism.”

The Populists' lives and social order was being forcefully reorganized without their consent. Established political institutions, methods, and beliefs quickly became irrelevant. “Populists brooded about the irrelevance of the inherited political dialogue of the nation. Their questions went beyond what capitalists were doing to farmers to include what the new ethos of corporate privilege was doing to the soul of America.” (Goodwyn)

“Indeed, to most Populists, the entire shape of American democracy seemed to have changed in the space of their own lifetimes. Virtually every line of the Omaha Platform reflected the belief that the very precepts of the schoolroom and the church had been made to count for nothing. What was democracy when aggressive 'captains of industry' could buy whole legislatures and keep the United States Congress in a perpetual state of genteel servitude? What was honest labor when ruthless structuring of the currency drove the price of farm products below the cost of production? What was thrift when high interest rates gobbled up farmland or when railroads made more money shipping corn than farmers did in growing it? Where was community virtue when bankers, commission houses, and grain elevator companies wantonly destroyed self-help farmer cooperatives? Where was dignity when farm women were forced to go barefoot and the furnishing man determined what a farmer’s family could or could not eat? Where was freedom when the crop lien system was enforced by the convict lease system? What did the old virtues mean, in such a setting?” (Goodwyn)

Most essentially, the Populists understood control of technology, the telegraph and railroads used by the banks to organize and consolidate the money system and markets, were integral to reordering power. “The agrarian reformers attempted to overcome a system of finance capitalism that was rooted in Eastern commercial banks and which radiated outward through trunk-line railroad networks to link in a number of common purposes of America’s consolidating corporate community. ...As John D. Rockefeller had conclusively demonstrated in the course of creating the Standard Oil Trust, railroad networks were a central ingredient both in the combination movement itself and in the political corruption that grew out of monopoly.” (Goodwyn)

In response to this new societal organization initiated by the new corporate structure and industrial technologies, the Populists realized their inherited political traditions offered few answers. “James Murdock of the Progressive Farmer also located the cause of widespread hardship in the political backwardness of the nation’s leaders and party system. 'We are in the era of steam, railroad, telegraph and mammoth machinery. The financial system that answered to the age of the slow coach, sickle and spinning wheel will not respond to this. We have had a revolution in manufactures and transportation, and we must have a radical change in our financial system.'” (Goodwyn)

The Populists tried addressing these challenges in numerous ways, first creating the Farmers Alliance to collectively and democratically organize the independent farmers. They conceived a new money system, the Sub-Treasury plan with local banks distributedly located across the country, not consolidated in several cities on the East Coast. Money would in part be based on the farmers' land and crops, an exponentially more sound foundation than any crypto currency. Finally, the Populists entered the electoral political arena. “The substance of the third party’s experiment in a new political language for an industrial society was the belief that government had fallen disastrously behind the sweeping changes of industrial society, leaving the mass of the people as helpless victims of outmoded rules.” (Goodwyn)

In the end, organizationally, they were incapable of matching the growing power of the corporation and industrial technology. “The collapse of Populism meant, in effect, that the cultural values of the corporate state were politically unassailable in twentieth-century America... The 'money question' passed out of American politics essentially through self-censorship. This result, quite simply, was a product of cultural intimidation. In its broader implications, however, the silencing of debate about 'concentrated capital' betrayed a fatal loss of nerve on the part of those who, during Populism, dared to speak in the name of a people’s movement.” (Goodwyn)

The first move of any new established power is to end discussion about the organization of their power. The Populists had this discussion, a discussion about how democracy could survive a new technological era. For their efforts, they have basically been written out of American history, disappeared along with any discussion about the money system, but even more importantly any acknowledgment of the role technology plays in establishing political order. Any understanding of technology as politics disappeared with them just as industrial technology fundamentally reshaped the 20th century.

Across the 20th century, a handful of thinkers attempted to explore the political implications of technology, yet their thought remained largely insignificant in denting the schools of economic thought, the culturally dominant political thinking established to shape and value industrial society, a thinking that ignored the political basics of industrial organization, most especially the power of the corporation.

The very real politics of technology became insignificant in relation to the mystical, deified forces of supply and demand. It is not an accident that thinkers such as Thorstein Veblen, Norbert Wiener, Marshall McLuhan, Jane Jacobs, Lewis Mumford, Ivan Illich and others remain largely unknown, their thinking of insignificant influence. Together, they laid a path to develop a politics of technology. A school of thought essential to in any way understand or shape human affairs of the 21st century.

In the Western tradition, beginning with the Greeks, it is thought that a greater understanding of the world, knowledge, was always a virtue. This Greek ethos laid the foundation of Western scientific thought. Two thousand years after the Greeks, a renaissance of Greek thought combined with Europe's adoption of Indian numbers and Arab math, sparked the Scientific Revolution. The Ancient Greek ethos that all knowledge was a virtue forcefully reasserted itself, directly transferring itself to the development of technology. Just as it was thought more knowledge was an unmitigated good, so too the ability to create any given technology was accepted uncritically. By the 20th century, technological development became exclusively valued by culturally dominant industrial economic values, capitalist or socialist, with little or no understanding that every technology asserted values of the technology itself.

One of the greatest early critics of developing 20th century economics, Thorstein Veblen, in The Place of Science in Modern Civilization (1919), understood the uncritical acceptance of unlimited knowledge as a virtue hindered the ability to critically analyze technology. He wrote,

“This is the one secure holding-ground of latter-day conviction, that 'the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men' is indefeasibly right and good. When seen in such perspective as will clear it of the trivial perplexities of workday life, this proposition is not questioned within the horizon of the western culture, and no other cultural ideal holds a similar unquestioned place in the convictions of civilized mankind.”

Veblen wrote as industrial technologies fundamentally shifted the shape of life in America. He correctly tied the unquestioned virtue of unlimited knowledge to the development of industrial technology and the culture it was creating. In a speech four decades later, one of the founders of the new era of quantum technology, nuclear physicist and technologist, J. Robert Oppenheimer noted “the phrase the ethical neutrality of science must be a fairly empty one, as an occupation it is based on a very clear belief that is good to know.”

Veblen explains the inability to develop critical science and thus a sophisticated value of technology, leads to what he calls a “matter-of-fact” system of technological development. This is the same understanding communications scientist Norbert Wiener addressed in 1948 using the term “know-how.” In both cases it is the simplistic engineer’s appraisal of technological development as a process of A + B = C. Such an exclusive process, Veblen and Wiener similarly conclude, eventually leads to technology developed exclusively for the sake of technology. Veblen writes,

“But the canons of validity under whose guidance he [scientists and technologists] works are those imposed by the modern technology, through habituation to its requirements; and therefore his results are available for the technological purpose. His canons of validity are made for him by the cultural situation; they are habits of thought imposed on him by the scheme of life current in the community in which he lives; and under modern conditions this scheme of life is largely machine-made. In the modern culture, industry, industrial processes, and industrial products have progressively gained upon humanity, until these creations of man's ingenuity have latterly come to take the dominant place in the cultural scheme; and it is not too much to say that they have become the chief force in shaping men's daily life, and therefore the chief factor in shaping men's habits of thought. Hence men have learned to think in the terms in which the technological processes act. This is particularly true of those men who by virtue of a peculiarly strong susceptibility in this direction become addicted to that habit of matter-of-fact inquiry that constitutes scientific research.”

A few years later, the great thinker on technology, Marshall McLuhan, would more succinctly put Veblen's above observation as first we shape technology and then technology shapes us. In refusing to acknowledge a politics of technology, homo sapiens becomes a product of technology.

Politically, industrial and now quantum technologies produce greater and greater centralization of political, economic, and cultural power. In 1950, Brave New World author Aldous Huxley writes in his essay Science, Liberty, and Peace,

“James Mill believed that, when everybody had learned to read, the reign of reason and democracy would be assured forever. But in actual historical fact the spread of free compulsory education, and, along with it, the cheapening and acceleration of the older methods of printing, have almost everywhere been followed by an increase in the power of ruling oligarchies at the expense of the masses.”

To “older methods of printing” can now be added broadcast media, digital communications, and their resulting technology oligarchies. Huxley warns, “Progressive technology has persuaded the many that concentration of political and economic power is for the general benefit.”

Huxley writes industrial technology based exclusively on economic values facilitates centralization: “There has been more money in working for the mass producers and mass distributors; and the mass producers and mass distributors have had more money because financiers have seen that there was more profit for them, and more power, in a centralized than in a decentralized system of production.”

A quarter century later, Goodwyn wrote: “The more germane historical reality is that centralization of American farmland had occurred even before corporate farming could prove or disprove its relative 'efficiency.' It was simply a matter of capital and the power of those having capital to prevent remedial democratic legislation.”

The development of economics has not been that of a science, but simply descriptions and justifications of the processes of industrialization. Its laws have more in common with the declarations of ancient priests upholding the rule of kings and emperors than any relationship to describing a natural force such as gravity. The silence in economics on the role of technology is deafening. Just as the Populists and Veblen, Huxley concludes our inability to devise a political understanding of technology gradually gives technology control of future development:

“For the present, Western societies remain at the mercy of their progressive technologies, to the intense discomfort of everybody concerned. Man as a moral, social and political being is sacrificed to homo faber, or man the smith, the inventor and forger of new gadgets. ...so long as the results of pure science are applied for the purpose of making our system of mass-producing and mass-distributing industry more expensively elaborate and more highly specialized, there can be nothing but ever greater centralization of power in ever fewer hands. And the corollary of this centralization of economic and political power is the progressive loss by the masses of their civil liberties, their personal independence and their opportunities for self-government.”

Our inability, more accurately our refusal, to develop a politics of technology has led to completely unaccountable technological development. In 1970, seminal politics of technology thinker Ivan Illich explained in Tools of Conviviality the inevitable path we've trotted, again a path the Populists clearly viewed almost a century before. Illich writes,

“Society can be destroyed when further growth of mass production renders the milieu hostile, when it extinguishes the free use of the natural abilities of society’s members, when it isolates people from each other and locks them into a man-made shell, when it undermines the texture of community by promoting extreme social polarization and splintering specialization, or when cancerous acceleration enforces social change at a rate that rules out legal, cultural, and political precedents as formal guidelines to present behavior. Corporate endeavors which thus threaten society cannot be tolerated. At this point it becomes irrelevant whether an enterprise is nominally owned by individuals, corporations, or the state, because no form of management can make such fundamental destruction serve a social purpose.”

He sums up both capitalist and socialist industrial politics: “People tend to relinquish the task of envisaging the future to a professional elite. They transfer power to politicians who promise to build up the machinery to deliver this future. They accept a growing range of power levels in society when inequality is needed to maintain high outputs. Political institutions themselves become draft mechanisms to press people into complicity with output goals.”

Illich concludes, “Our present ideologies are useful to clarify the contradictions which appear in a society which relies on the capitalist control of industrial production; they do not, however, provide the necessary framework for analyzing the crisis in the industrial mode of production itself.”

Here is the key. In analyzing the “industrial mode of production itself,” you need to analyze the technology itself. Our present political, our social ideologies, are not simply insufficient, but cripplingly tied to the past and detrimentally entrenched across society. Organizational understanding is crippled by the default order of hierarchy. Centralized control is perceived as the exclusive political method of organization. In contradiction, Illich, along with Veblen, Wiener, and Huxley, understood we needed to reassess our relation to science, most especially in regards to the future of humanity and technological development, science offers no future inevitabilities. “The vision of new possibilities requires only the recognition that scientific discoveries can be useful in at least two opposite ways. The first leads to specialization of functions, institutionalization of values and centralization of power and turns people into the accessories of bureaucracies or machines. The second enlarges the range of each person’s competence, control, and initiative, limited only by other individuals’ claims to an equal range of power and freedom.” (Illich)

Huxley similarly concluded, “There is nothing in the results of disinterested scientific research which makes it inevitable that they should be applied for the benefit of centralized finance, industry and government.” Today, science is used to constrain thought and validate centralized control. Veblen suggests a more holistic view of the implementation of science, one understanding science's cultural roots: “Such positive action may be classified under two heads: (a) action which takes its start in politics, to end in the field of science: and (b) action which takes its start in science, to end in politics.”

Thus, a group of 20th century thinkers understood science and technology had political implications, implications many scientists and technologists have not simply ignored but denied, most never even considering it. Our inability to evolve politics has led to an increasing centralization of power, a centralization more and more led by the demands of technology itself.

In recorded human history, centralized hierarchical order is the dominant organization of power across human society. Hierarchy has long been wrongly characterized as the “natural” order of power. Nature was repeatedly misinterpreted across history to validate centralized power much in the same way 20th century economics justified the concentrated power of the corporation. Physical power, most essentially the power to inflict one's will through organized violence became essential to hierarchical organization. Power backed romanticized notions of lions as the king of beasts, with little understanding the complexity of ecological systems. Power celebrated social dominance through physicality, ironically in a species overwhelmingly defined by information and communication. This simplistic and crude structuring of social order was detrimental and grows ever more destructive as technology became more powerful. In his A Primate's Memoir, neurologist Robert Sapolsky notes if a troop of baboons relied on the physically dominant male for finding food sources they would starve. Such order, the living knowledge within the troop, was provided by old females, the antithesis of a physically imposed dominant young male hierarchy.

Many of today's hierarchical traditions trace back ten-thousand years to what remains one of humanity's greatest technological eras, the domestication of plants and animals and the beginning of the Agrarian Age. This was a significant advance in human knowledge along with a growth in the quantity of information necessary to conduct daily human life. Previous to the Agrarian Era, humanity's several hundred-thousand years as hunter-gatherers, knowledge/information was largely equally distributed. Elements of life impacted a given social group simultaneously. There was no great advantage or even an ability to store or control information outside the person. Just as with a baboon troop, knowledge beyond daily occurrence was stored in memory, giving older persons a degree of social standing.

With the Agrarian Era, knowledge and information increased, most essentially the knowledge of the right times to sow and reap. The first science was gained from an understanding of the movement of the moon, planets, and stars. Control of the resulting calendar became a lever of power. Gradually, agrarian societies producing excess foodstuffs allowed greater and greater concentrations of population. With this concentration came ever more sophisticated social organization, requiring more information and communication. The ability to order this information and communication were used as levers to establish hierarchical, centralized control. In return, organized central power — culturally, politically and economically — justified the centralized organization of power.

Ancient Greek thinking laid the foundation to what eventually developed into the scientific method. Oppenheimer noted the Greeks added to human observations of nature a certain rigor, a valuing of the ability to repeat. In looking at the development of our matter-of-fact/know-how preeminent technological ethos, the practice of rigor, the ability to repeat scientific observation was essential to gaining the knowledge and capabilities necessary to create the technology surrounding us. The matter-of-fact/know-how approach, allows a simplistic, part by part understanding, opposed to what is the greater complexity and meaning of any system as a whole, for example looking only at the kidney in trying to understand the human body or at one species to define the entire ecological system it is part.

In practice, this know-how approach blinds us to greater meaning, automatically constraining our view to largely finding only what we set out to look for. This becomes not simply problematic but detrimental for today's technologically shaped society. The constrained limited know-how used to develop a given technology becomes locked into that technology. As a technology becomes not just a greater part of the society, but an essential force shaping the society, this constraint defines society and restricts future development of technology by both limiting alternative thinking and prejudicing future development to what already exists.

Looking at the established organization of political power and the inclusive interaction between the physical, energy, and information, nothing is more revelatory than America's food system. The beginning of this piece documented the industrialization and consolidation of American agriculture. The resulting present system reveals the physical components, such as concentration of land ownership; tractor, truck, and equipment manufacturers; tied together by roads, railroads, and global grain ships. From an energy perspective, the entire system is soaked in fossil fuels, not simply in powering the tractors or getting harvests to national and global markets, but in the creation of fertilizer, pesticides, and herbicides. A system that went from including over half the population in farming a century ago to today where less than 2% are directly involved.

The system became increasingly information rich, not just in all aspects of organizing this vast consolidated system, but in the knowledge essential for continually changing pesticides and herbicides in response to insects and plants evolving in reaction to their overzealous application. In recent years, control of the engineering of plants and animals at the genetic level create an ever more essential information component of the system controlled by a handful of corporations seeking greater power over life at one of its most fundamental levels. Finally, a handful grocery companies deliver the majority of food, a distribution system reliant on the automobile.

With the industrialization of the small farm and resulting population migration to urban areas, organization of physical locality, personal movement, once defined by either foot or horse, was transformed by the automobile. For American life, the car became a seemingly existential necessity. American car culture saw people's economic, political and cultural affairs designed around the car. A handful of automobile companies and oil companies became powers nationally and globally, with smaller companies, responsible for the automobile street infrastructure rising as local powers. The automobile consolidated the distribution of all goods, both necessities and advertising-driven consumption. The pinnacle of centralized automobile distribution came with the suburban mall made possible by automobile-created suburban housing, drawing consumers from miles around, spread across their individual manicured landscapes.

In the last decade, the development of compute information technologies saw the first challenge to the societal organizational hegemony of the automobile. The “Amazon distribution” system challenged the decades-old car model distribution. This new system was made possible by information technologies, by the internet. Instead of stores within relatively short driving distance or massive malls farther spaced, the Amazon model sees numerous large distributed warehouses storing goods. These warehouses are geographically organized to allow a certain efficacy in delivery by trucks moving door to door. Whether this is a more efficient process in regards to energy use than established auto-centric distribution is unclear (I've seen no comparative numbers). However, it is without a doubt far more energy wasteful than a distribution system with the final leg of distribution reliant on the human body unaided by other external energy sources, for example, local stores organized in walking or biking distance.

The second threat to dominant car culture has also been made possible by information/communications technologies. This has been the growth of “remote working,” catalyzed by the Covid disruption. This has seen a hollowing out of office centers, themselves creations of the 20th century information wave. It has not yet seen a corresponding reorganization of other social activities based around the increased presence of individuals in their homes. For the most part it has only led to a greater increase in online communication, handing ever more power to tech-information companies.

The Amazon distribution model and work at home movement reveal the increasingly dominant role information technologies now play shaping both locality and energy use, the manifestation of information. In a relatively short period of time, this reorganization by information technologies has made Amazon massively powerful, a power comprising physical, energy, and information organization. At this point, “internet” is used offhandedly to refer to what is a plethora of networks sharing many of the same technical standards, but nonetheless separately organized. For example, the internal network of a corporation may run through the internet with its internal communication and data “walled-off” from the outside. Customers place their data on centralized corporate controlled servers, euphemistically marketed as “the cloud,” now including centralized compute power marketed as AI, all connected via the internet. Increasingly, the engineered internet has more in common with the old mainframe model of central server and dumb terminals than any massively distributed network as first promoted. The networks are engineered both internally and in their connections to society's greater physical and social structures, facilitating further central control. Thus, there is the power of the networks' actual organization and the power of how the networks connect to what is increasingly every aspect of society.

Today, America's once largely distributed yeoman farm republic is now an industrial, centralized, increasingly information rich, corporate oligarchy. The exceptional order of distributed democracy now entirely replaced by traditional hierarchical organization wielding new tools.

In the last century and half, starting with the biology of Charles Darwin's natural selection and continuing with relativity and quantum physics, an antithetical view of centralized order came to be better understood. A world, a universe not of centralized, hierarchical, top-down order, but one infinitely distributed, networked, and dynamically interacting. Order rose not from a powerful centralized top but through innumerable interactions at multidimensional levels. As an analogy to social organization, it is order much more resembling historically exceptional democracy than our entrenched traditional hierarchy.

In a wonderful book, Metazoa: Animal Life and the Birth of the Mind, University of Sydney Professor Peter Godfrey-Smith looks at the organization inherent in all life. From the beginning of life on this planet, every single celled organism, the biggest dinosaurs of a hundred million years ago, and ourselves today have been organized by information and the processes of communicated information. Smith makes a sublime association between objective, naturally engineered organization, and the subjective meaning of communication. He writes, “Point of view has always been metaphorical, but it suggests a lot of integration.” By integration he is talking about the organization of any organism in its abilities to process information. This organization can be separate, done through different channels or integrated, where information flows together, internally “many animals are only partially integrated.”

When an organism's inherent organization separates the streams of information, what it collects from various senses, “you tend to gain some things―often you may gain speed―and lose some things. If sensory streams are separated from each other, you lose the ability to combine different kinds of information that might be useful when considered together, like the many premises of an argument or many pieces of a puzzle. If you allow different parts of yourself to perform their own actions, you risk a situation where your active parts want to do contradictory things. In the extreme, you risk fragmenting entirely, into sub-agents who see their own scenes and make their own decisions. That certainly looks like a bad idea, but we should not assume that everything follows a shape with a central CEO and a lot of underlings.”

This separation of sensory channels can be looked at as analogous to the organizational model for modern human society from Adam Smith's division of labor to the extreme specialization at the top of academia. By organizing specialization and division, we socially engineer subjectivity. Society, life itself, seen and experienced through very narrow informational bands with little integration. With the power of the modern mega-corporation and centralized government, we attempt, increasingly failingly, to tie things together under CEOs, whether as heads of giant corporations or presidents in white houses. Such institutions and people are parts of failing hierarchies, unnatural orders incapable of effectively tying things together, much less to in any aesthetic way integrate the multifarious channels that comprise societal order. This organization overwhelmingly breeds prejudiced subjectivity; the semantics of all information communicated limited in its interpretation.

We hold larger centralized nervous systems, biological engineering to process both quantity and quality of sensational information, as indicators of greater intelligence. Of course, such valuing places ourselves at a subjective top. Godfrey-Smith writes, “Octopus embody a design very different from our own. The octopus nervous system is decentralized; about two thirds of the neurons are not in the brain (itself a vaguely defined region), but the arms, especially in the upper arms. These act not just as outlying sensors and relay systems feeding the central brain; there is an apparent delegation of the control of some motions to the arms themselves.”

The octopus upsets our wrongful prejudice of the necessity of a centralized hierarchical brain.

“A decentralization of the body's controllers is seen not only in the octopus. Forms of it are found in many animals, including ourselves, and there are reasons why this might be expected to some extent. The features of animals that are responsible for sensing and action, the features whose history I have been charting, are complicated and require many parts. Organized arrays of cells are needed for seeing, other arrays of cells are needed to produce movement, and nervous systems with still more cells are needed to coordinate it all. Once you have all this machinery, you have some new evolutionary options. You can separate out some pathways, create local lines of control. It becomes a choice, in an evolutionary sense, whether you create separate streams that control action or integrate everything into a single stream. You can also do a bit of both; you can have largely separate tracks with some cross-talk between them.” (Godfrey-Smith)

Godfrey-Smith documents life as organization, every aspect of it from a single cell to the complex nervous system of the octopus. With organization, the engineering defines how information is processed, from which is derived semantics.

Looking not at organisms, but at the body politic, organization is just as essential to how we process information. Organization designed by information to process other information. Godfrey-Smith writes, all organization determines future possibilities. In this still new technological era, the control of nascent information technologies by a handful of massive corporations using centralized networks coordinated by massive data “centers” limits our ability for future options. Politically, these new centrally controlled information systems make democracy impossible.

Using knowledge gained from 20th century physics, humanity innovated compute technology and the transistor leading to an exponential increase in information and communication. Norbert Wiener, the great 20th century thinker on information systems, stated, “Information is information, not matter or energy.” Like much physics, we define information more in what it does, in know-how, as opposed to know-what. Matter, energy, and information are intertwined in all aspects of human existence, essential components of all life. At the beginning of the 20th century, Einstein revealed energy and matter to be equivalent. A small amount of matter consisted of inconceivable quantities of energy. To manifest, be utilized, information must take the form of energy or matter — an essential understanding for any politics of information technology.

Information has always been at the core of defining homo sapiens. As social beings, communication, the transference of information, is essential to who and what we are. The control of information and its communication has been a key component of all hierarchy across human history. Nonetheless, our definition of information remains rather nebulous.

In his introduction to Claude Shannon's The Mathematical Theory of Communication, Warren Weaver sums up Shannon's thinking, “Just as the amount of information in a system is a measure of its degree of organization, so the entropy of a system is a measure of its degree of disorganization; and the one is simply the negative of the other.” Shannon's math underlies the structure and processes of all recent information/communication technologies. Most intriguing and valuable is the idea that information is valued through its organization. Whether as energy or matter, this information organization is accomplished via communication.

Shannon states, “The semantic aspects of communication are irrelevant to the engineering aspects.” Using this definition, control of information has two aspects. One is the actual structures of communication, that is the engineering. The second is the meaning, the semantics. The former is objective, the latter always contains elements of subjectivity. While the engineering of communication can be straightforwardly conceived, the meaning derived from what's communicated much less so, no matter how much effort those in control attempt to restrict meaning.

Both the engineered structure and semantics are politics. In both respects, this bifurcated control of information has been fundamental to the organization of family, tribe, nation, and empire. In hierarchical order, communication is engineered to allow a small centralized top control an exponentially larger bottom. This is the objective communication structure of oligarchy, monarchy, and tyranny. Democracy requires more distributed communication order. The Greek and Roman citizen assemblies, the distributed level system of the American republic from local to federal, the Bill of Rights' declaration of freedom of the press, are all examples of objectively engineered distributed communication organization. Such openly engineered systems are fundamental to any notion of self-government. The organization of the processes, technologies, and institutions of communication are essential politics, regardless of any and all ideas passed through them.

Reviving democracy would require a complete reorganization of society, an engineered redistribution of power. Simultaneously, the increasing adoption of technologies based on a greater knowledge of the distributed order of nature, such as information technologies, genetic manipulation, and the latest mad rush to nuclear power in both weaponry and energy production to power an exponential increase in centralized compute power, makes centralized control not simply politically problematic, but raises serious questions about its ability to control the technology itself in regards to stability and viability.

Wiener's insight that information is neither energy nor matter, combined with the understanding that information manifests itself in human experience in its ability to organize energy and matter, is a valuable starting point for thinking about restructuring politics. At its most fundamental level, human society organizing matter and energy is politics. Rethinking political organization begins with understanding social organization which includes the organization of matter, energy, and information.

Democracy is the most useful organizational and processing system for a human society awash with what for the individual might as well be an infinite quantities of information, quantities making it simply impossible for an individual to grasp, much less process. Democratic politics need a distributed structured system, a system having more in common with the participatory systems of Athens and Rome than the representative system of modern republicanism. A system where a central meeting place for the entire citizen body, such as Roman forum or the Athenian ekklesia, isn't necessary, but where innumerable smaller participatory nodes are networked together via multiple channels, allowing both deliberation and action by the nodes and the individuals comprising them.

All politics begins with local geographic characteristics. Homo sapiens remain biological organisms shaped by the environments they inhabit. The planet we collectively inhabit is composed of local areas of both advantageous and disadvantageous characteristics. Industrialization flattened out many of these disparate characteristics, creating homogenization. Industrial technology allowed a radical overriding of locality, for example creating a similar technologically produced environment whether you lived in the suburbs of Boston, Phoenix, or Seattle. In fact, traveling the world, you can find similar or exactly the same daily living conditions – climate control, automobile centered transport, diet, and entertainment – provided by the same corporations, whether living in Lagos, Tokyo, Rome, Lima, or Moscow.

Can we instead apply the knowledge we've learned over the last century of nature's distributed order to our societal order – cultural, political, economic and technological? Reorganizing literally from the ground up, society’s physical, energy, and information components, a reorganization incorporating an understanding all such structures are politics. We still have an enormously limited understanding of distributed order, a still greatly undeveloped notion of possible democratic order, an understanding with no sense of the importance of technology. Democratic order needs continuous, egalitarian communication between all elements. Evolving democracy requires the purposeful distributed networked organization of the physical, energy, and information, and an intertwining across innumerable networks comprised of all three.

The composition of such networks would be people organized into a variety of associations – cultural, political, and economic. These associations would function as nodes of massive globally connected distributed networks. Foundationally, these associations would be locally defined, incorporating the advantages and disadvantages of the local elements of geography, weather, and ecology. They would take into account how a person physically interacts with these elements and just as importantly how each person in a given locality interacts with other people – culturally, politically, and economically.

The fundamental structure of democracy is face to face meetings where information is directly communicated and discussed from individual to individual or individual to group or group to group. It also includes organization of the production and the distribution of necessities, such as food and clothing. A purposeful physical organization facilitating communication between individuals and their physical activities such as gathering together or picking up necessities where a person can walk or bicycle using the least amount of exogenous energy. As Illich in maybe his most sublime insight noted, “Participatory democracy demands low-energy technology, and free people must travel the road to productive social relations at the speed of a bicycle.”

Key to understanding the above paragraph are the relationships between people without intervening media. All media – Webster: “something in a middle position” – intrudes some organization of power. Obviously this doesn't mean democracy requires civilization without media, in fact, for better and worse, what we conceive of civilization is media. However, the naked individual as a member of whatever human organization is the most fundamental level of power, where each member of any combined social organization has equal say in any group decision is elementary democracy. The placing of any and all media between individuals and groups always adds another element of power. The organization of the medium itself and how the people interact with the medium always add elements of power. If the social organization with the introduction of any medium is to be democratic, both the medium and resulting organization need to be democratically structured.

Distributed networked nodes can be permanently structured together, defined geographically such as all nodes around a lake, a river basin, those sharing a desert plain, or regionally created with the assistance of various media in the case of neighborhoods of a city. These associations can also form temporary coalitions, such as cities working collectively together creating and connecting to greater energy and transportation infrastructures, a fundamentally different process for example than the present process where cities in the US need to work at the state or federal levels to act together. Here state and federal organization become media intruding their own power, often overriding the power of the locality. Instead, associations can be of countless varieties distributedly connected not simply by location, but all issues of concern, order can be provided without centralization. Order is defined in the connections.

Whatever the concerns of any given node and network, the creation, editing, and communication of information will be a primary concern. Today, as the individual is drowned in a tsunami of information, it is impossible for any person to utilize information in all but an extremely limited, a specialized sense. Outside individuals comprising the divided specialized professions, “experts,” be they a lawyer, doctor, or engineer and the information they are directly able to manipulate, overwhelmingly all people are simply consumers of information. All individuals, including the specialized, are powerless in regards to news of their communities, nations, and the planet. This is a result both of the centralized architecture of the new compute technologies and the entrenched industrial order which allows no participation outside specialized inputs and mass consumption.

An important note here needs to be made about consumption. There is no argument industrialization created a cornucopia of consumer stuff, both necessities and more than plenty not so necessaries. While control of the production processes was overwhelmingly centralized, there is without a doubt a certain democratic element to mass consumption. As the sublime Modern artist Andy Warhol quipped, “Everyone drinks the same Coke.” However, this paper is concerned not simply with the product of consumption, but who controls and decides what and how things are produced, most especially what is the role of the individual in these processes. A revival of politics where the role of the individual is not simply a cog in production with the only reward consumption, but as a decision maker helping design the life they live and are part.

Just as a hundred thousand years ago, the individual was reliant on their social group for survival, today every individual relies on organization to make any sense of the data deluge. However, the processes providing useful information are overwhelmingly hierarchically controlled, from Federal bureaucracies to massive corporations like Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Facebook, or any number of industrial corporations. The ever more powerful information conglomerates now seek to automate decision processes, marketed as AI, removing individual control and simultaneously entrenching existing power, resulting in unprecedented prejudicial control of the future.

The Agrarian Age saw the reorganization of the physical environment, of locality, as society's greatest mover. The Industrial Era witnessed the mass harnessing of energy to reshape and homogenize society. Both were reliant on information to manifest. In each of these eras, shaped by new technologies, human activity radically changed: first from hunter-gatherers to farmers, then from farmers to factory laborers. Now in the era of compute technologies, humanity spends more time creating, processing, communicating, and acting on information. Certainly, if it continues on the course established, and that is doubtful for a number of reasons including energy needs and systemic stability, centrally controlled automation will grow. In opposition, people can be directly organized into the process, both as individuals and as collective democratic associations, organized around creating, editing, and communicating information, and most essentially deciding.

Just as the main concern of the Agrarian Era individual was farming, the laborer of the Industrial Era, this Information Era will require individual concern, identity, in today's popular and not so insightful political parlance, in the creating, editing, and communicating information. In this regard, people need to be valued for their informational roles without devaluing both their roles and the information by necessitating monetization as the only means to provide value. During the Agrarian Era, the vast majority of people were valued not monetarily, but by their roles in society as farmer, merchant, or craftsperson. Industrialism manufactured the overwhelmingly dominant and almost exclusive societal valuing through monetization. There is no need to monetize most information. New values need to develop, including valuing every individual as a creator, editor, and communicator of information. Money itself needs to become a more information rich medium.

Many of these values will be created, learned, and their merit accessed through the organization itself, most essentially via participation. Elections are essential to democracy. They are a non-monetary valuing system, one of few left existing today, though it's very difficult to look at today's money bought, reality television election process as a system providing any democratic value.

One part of the present system that can be exponentially expanded is the jury system. The jury system goes back at least two and half thousand years to the Ancient Greeks. Juries can be vastly expanded to make all systems more accountable, bringing back a form of the Ancient Athenian accountability system of euthenya. This was the process begun after any magistrate held office. It was an auditing, both fiscal and procedural, to hold account the magistrate's actions in office. All magistrates served only one year, most selected by lot. In modern republicanism, elections were thought to provide accountability, but have proved completely insufficient. Our mega-corporations, it is preached by our economist priesthood, are supposedly held to account through markets or via government regulation, systems the corporations control. Such unaccountability makes the fundamentally undemocratic structure and processes of contemporary power crystal clear. The most elementary process separating democracy from tyranny is holding power accountable. If power isn't accountable, there is no self-government.

A model of the jury system can be expanded to include interpretation of all laws, replacing the far too dominant judicial process now run by judges, most egregiously represented by the unelected nine member Supreme Court and their thunderous marbled hall proclamations of order. Instead a widely distributed jury system would be an organization seeking to make law more dynamic, not that of traditional hierarchical law seeking to be permanently etched in stone, but more similar to the dynamic interaction of living systems. “Information is even more a matter of process than a matter of storage.” (Wiener)

Information and its communication must be freed from constraints of corporate ownership, such as patents and copyrights, and not stored lifeless in massive data bases, but allowed to live dynamically across multitudes of associations with their actions and in the very organization of the networks they form. An evolved jury system can be looked at as decision making bodies, part of associations valuing information based on precise content and allowing decisions to be made on this information.

Imagining such change immediately envisions much greater complexity, yet it is a complexity inherent in the organization of nature and, importantly, increasingly in the technology we create. In creating distributed networked systems, another recent scientific discovery may be the most important. The process of feedback must be engineered into all democratic structures. Feedback is defined here as a simple return of information based on information communicated or an action taken.

Norbert Wiener was one of the first to understand the importance feedback played as an essential element for life systems and to understand it would be an imperative component of any automated system. Wiener states, “It is certainly true that the social system is an organization like the individual, that it is bound together by a system of communication, and that it has a dynamics in which circular processes of a feedback nature play an important part.” Feedback is an imperative part of all political systems. No political system, no matter how autocratic, survives without feedback. However oligarchic/tyrannical power structures have massive channels of communication transmitting from the top, their feedback channels narrow and extremely limited. Just as importantly, feedback in such centralized systems are not valued for change, but for tamping or stomping down dissent of the established order. In a distributed network, feedback becomes essential for order, channels of return are equal in volume and force as those initiating the signal, be it information or an action.

Distributed networks are much more dynamic, capable of quickly enacting and reacting to signals sent and actions taken. Such networks are basically alive, quite the opposite of centralized industrial systems where for example feedback to the changes wrought on ecological systems were largely absent or ignored. Our archaic systems of government, encased in cold marble, where the past is worshiped not utilized, can evolve into dynamic living systems meeting the unending challenges and the joy and tragedy of life.

“The Populists had dared to pursue cultural acceptance of a democratic politics open to serious structural evolution of the society.” Lawrence Goodwyn

“The most socially desirable power of a tool can only be the outcome of political procedure.” – Ivan Illich

“The political importance of the township was never grasped by the founders, and that the failure to incorporate it into either the federal or the state constitutions was 'one of the tragic oversights of post-revolutionary political development'.” – Hannah Arendt, On Revolution, 1963

Across the globe, politics grows increasingly impotent to meet the challenges humanity faces in the 21st century. Our political institutions are archaic, while politics inherent in all organization are largely ignored or placed in stringent categories considered nonpolitical. Today, politics’ greatest deficiency is an incredible ignorance of the role technology plays in shaping society, despite the fact from homo sapiens rise on the African continent, our growing knowledge and the resulting technology shaped our lives.

In the last two centuries, the growth of human knowledge about nature's order has grown exponentially. This expansion of scientific knowledge led to an explosion of powerful technologies with the Industrial Revolution. Our ability to harness the power of burning fossil fuels changed the landscape of the planet, reorganizing human life and the ecologies shaping us more than anything since the Agrarian revolution ten thousand years before.

Simultaneous with the Industrial Revolution, though in no way cause and effect, was the birth of modern republicanism with the founding of the United States. This political order was based on the agrarian culture about to be largely swept aside as industrialism arose to dominate. While republican institutions, always anomalies in recorded human history, were radical in their reintroduction in opposition to then established monarchical order, however, they proved completely insufficient to meet the onslaught of change introduced by industrial technologies.

With industrialization came a resurgence in the modern republic of the very old human tradition of reliance on centralized hierarchical order, most especially with industrialism's only real social innovation — the corporation. The reintroduction of republicanism created a revolutionary political atmosphere for two centuries across the planet's agrarian cultures. Yet, the distributed order of modern republicanism was largely still-birthed. Politics increasingly became about swapping out the top of largely or exclusively ordered hierarchical systems to pull already established levers of power in the name of change.

This fight for the centralized top was best exemplified with the 20th century communist revolutions, the only political ideology to be formed, or better malformed, directly from an ideology created by industrialization. Despite both the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and The People’s Republic of China's use of republic in their official names, both quickly adopted centralized rule. However, some Bolsheviks, such as Lenin and Bukharin, also had ideas of a more decentralized order. Ascending to the top of a two and half thousand year old hierarchical civilizational order, Mao understood in thought, certainly not always in deed, all true revolutionary change would mean distributing power. Of course a steel foundry in every backyard may not have been the best leap forward, it was thought wrestling with decentralized industrial order.

The US represented industrialization destroying the agrarian republic, its politics eventually becoming nothing more than a personal fight over who controls Washington DC, even worse an obsession with who controls the White House.

Now a new information/communication/compute technology revolution upsets the established hierarchies of industrialism and the remaining older hierarchies of agrarianism. However, these technologies are not used to create a new more distributed order with the knowledge of the physical and biological sciences from which they have been derived. Instead, as with industrialism, this new technology empowers newer, even more centralized hierarchies. Most disconcerting, the centralized control being imposed by this technology is highly questionable in its ability to sustain further technological development or the vitality of the current technology, not even considering its impact on humanity's social order or the health of the planet's ecologies.

In direct opposition to humanity’s long deification of technology, we are in need of creating a completely secular and healthy politics of technology. A politics that places humanity above technology, that acknowledges technologies as useful tools. Technology's impact on social organization must be understood and designed to just as great a degree as the know-how responsible for creating the technology itself. The revival of politics requires an accompanying appreciation of the worth of every individual, an understanding designing new social organization needs a democratic structure of distributed power allowing both individual and egalitarian collective initiative.